Recently I asked on Twitter what the next RD News post should be about.

Seems you want to hear about upcoming new features, so… here it goes!

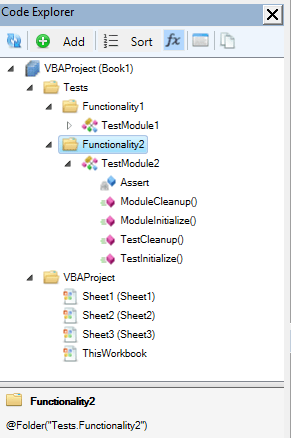

The current build contains a number of breakthrough features; I mentioned an actual Fakes framework for Rubberduck unit tests in an earlier post. That will be an ongoing project on its own though; as of this writing the following are implemented:

- Fakes

- CurDir

- DoEvents

- Environ

- InputBox

- MsgBox

- Shell

- Timer

- Stubs

- Beep

- ChDir

- ChDrive

- Kill

- MkDir

- RmDir

- SendKey

As you can see there’s still a lot to add to this list, but we’re not going to wait until it’s complete to release it. So far everything we’re hijacking hooking up is located in VBA7.DLL, but ideally we’ll eventually have fakes/stubs for the scripting runtime (FileSystemObject), ADODB (database access), and perhaps even host applications’ own libraries (stabbing stubbing the Excel object has been a dream of mine) – they’ll probably become available as separate plug-in downloads, as Rubberduck is heading towards a plug-in architecture.

The essential difference between a Fake and a Stub is that a Fake‘s return value can be configured, whereas a Stub doesn’t return a value. As far as the calling VBA code is concerned, that’s nothing to care about though: it’s just another member call:

[ComVisible(true)]

[Guid(RubberduckGuid.IStubGuid)]

[EditorBrowsable(EditorBrowsableState.Always)]

public interface IStub

{

[DispId(1)]

[Description("Gets an interface for verifying invocations performed during the test.")]

IVerify Verify { get; }

[DispId(2)]

[Description("Configures the stub such as an invocation assigns the specified value to the specified ByRef argument.")]

void AssignsByRef(string Parameter, object Value);

[DispId(3)]

[Description("Configures the stub such as an invocation raises the specified run-time eror.")]

void RaisesError(int Number = 0, string Description = "");

[DispId(4)]

[Description("Gets/sets a value that determines whether execution is handled by Rubberduck.")]

bool PassThrough { get; set; }

}

So how does this sorcery work? Presently, quite rigidly:

[ComVisible(true)]

[Guid(RubberduckGuid.IFakesProviderGuid)]

[EditorBrowsable(EditorBrowsableState.Always)]

public interface IFakesProvider

{

[DispId(1)]

[Description("Configures VBA.Interactions.MsgBox calls.")]

IFake MsgBox { get; }

[DispId(2)]

[Description("Configures VBA.Interactions.InputBox calls.")]

IFake InputBox { get; }

[DispId(3)]

[Description("Configures VBA.Interaction.Beep calls.")]

IStub Beep { get; }

[DispId(4)]

[Description("Configures VBA.Interaction.Environ calls.")]

IFake Environ { get; }

[DispId(5)]

[Description("Configures VBA.DateTime.Timer calls.")]

IFake Timer { get; }

[DispId(6)]

[Description("Configures VBA.Interaction.DoEvents calls.")]

IFake DoEvents { get; }

[DispId(7)]

[Description("Configures VBA.Interaction.Shell calls.")]

IFake Shell { get; }

[DispId(8)]

[Description("Configures VBA.Interaction.SendKeys calls.")]

IStub SendKeys { get; }

[DispId(9)]

[Description("Configures VBA.FileSystem.Kill calls.")]

IStub Kill { get; }

...

Not an ideal solution – the IFakesProvider API needs to change every time a new IFake or IStub implementation needs to be exposed. We’ll think of a better way (ideas welcome)…

So we use the awesomeness of EasyHook to inject a callback that executes whenever the stubbed method gets invoked in the hooked library. Implementing a stub/fake is pretty straightforward… as long as we know which internal function we’re dealing with – for example this is the Beep implementation:

internal class Beep : StubBase

{

private static readonly IntPtr ProcessAddress = EasyHook.LocalHook.GetProcAddress(TargetLibrary, "rtcBeep");

public Beep()

{

InjectDelegate(new BeepDelegate(BeepCallback), ProcessAddress);

}

[UnmanagedFunctionPointer(CallingConvention.StdCall, SetLastError = true)]

private delegate void BeepDelegate();

[DllImport(TargetLibrary, SetLastError = true)]

private static extern void rtcBeep();

public void BeepCallback()

{

OnCallBack(true);

if (PassThrough)

{

rtcBeep();

}

}

}

As you can see the VBA7.DLL (the TargetLibrary) contains a method named rtcBeep which gets invoked whenever the VBA runtime interprets/executes a Beep keyword. The base class StubBase is responsible for telling the Verifier that an usage is being tracked, for tracking the number of invocations, …and disposing all attached hooks.

The FakesProvider disposes all fakes/stubs when a test stops executing, and knows whether a Rubberduck unit test is running: that way, Rubberduck fakes will only ever work during a unit test.

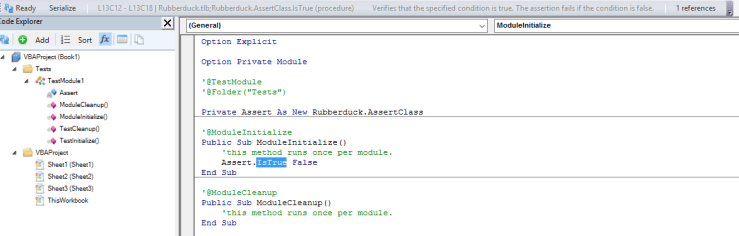

The test module template has been modified accordingly: once this feature is released, every new Rubberduck test module will include the good old Assert As Rubberduck.AssertClass field, but also a new Fakes As Rubberduck.FakesProvider module-level variable that all tests can use to configure their fakes/stubs, so you can write a test for a method that Kills all files in a folder, and verify and validate that the method does indeed invoke VBA.FileSystem.Kill with specific arguments, without worrying about actually deleting anything on disk. Or a test for a method that invokes VBA.Interaction.SendKeys, without actually sending any keys anywhere.

And just so, a new era begins.

Awesome! What else?

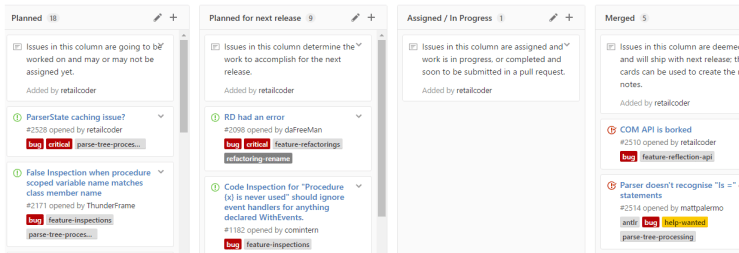

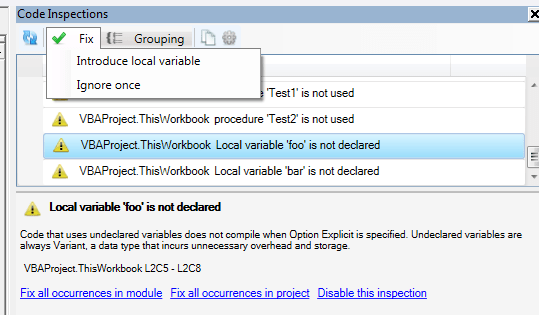

One of the oldest dreams in the realm of Rubberduck features, is to be able to add/remove module and member attributes without having to manually export and then re-import the module every time. None of this is merged yet (still very much WIP), but here’s the idea: a bunch of new @Annotations, and a few new inspections:

MissingAttributeInspectionwill compare module/member attributes to module/member annotations, and when an attribute doesn’t have a matching annotation, it will spawn an inspection result. For example if a class has a@PredeclaredIdannotation, but no correspondingVB_PredeclaredIdattribute, then an inspection result will tell you about it.MissingAnnotationInspectionwill do the same thing, the other way around: if a member has aVB_Descriptionattribute, but no corresponding@Descriptionannotation, then an inspection result will also tell you about it.IllegalAnnotationInspectionwill pop a result when an annotation is illegal – e.g. a member annotation at module level, or a duplicate member or module annotation.

These inspections’ quick-fixes will respectively add a missing attribute or annotation, or remove the annotation or attribute, accordingly. The new attributes are:

@Description: takes a string parameter that determines a member’sDocString, which appears in the Object Browser‘s bottom panel (and in Rubberduck 3.0’s eventual enhanced IntelliSense… but that one’s quite far down the road). “Add missing attribute” quick-fix will be adding a[MemberName].VB_Descriptionattribute with the specified value.@DefaultMember: a simple parameterless annotation that makes a member be the class’ default member; the quick-fix will be adding a[MemberName].VB_UserMemIdattribute with a value of0. Only one member in a given class can legally have this attribute/annotation.@Enumerator: a simple parameterless annotation that commands a[MemberName].VB_UserMemIdattribute with a value of-4, which is required when you’re writing a custom collection class that you want to be able to iterate with aFor Eachloop construct.@PredeclaredId: a simple parameterless annotation that translates into aVB_PredeclaredId(class) module attribute with a value ofTrue, which is howUserFormobjects can be used withoutNewing them up: the VBA runtime creates a default instance, in global namespace, named after the class itself.@Internal: another parameterless annotation, that controls theVB_Exposedmodule attribute, which determines if a class is exposed to other, referencing VBA projects. The attribute value will beFalsewhen this annotation is specified (it’sTrueby default).

Because the only way we’ve got to do this (for now) is to export the module, modify the attributes, save the file to disk, and then re-import the module, the quick-fixes will work against all results in that module, and synchronize attributes & annotations in one pass.

Because document modules can’t be imported into the project through the VBE, these attributes will unfortunately not work in document modules. Sad, but on the flip side, this might make [yet] an[other] incentive to implement functionality in dedicated modules, rather than in worksheet/workbook event handler procedures.

Rubberduck command bar addition

The Rubberduck command bar has been used as some kind of status bar from the start, but with context sensitivity, we’re using these VB_Description attributes we’re picking up, and @Description attributes, and DocString metadata in the VBA project’s referenced COM libraries, to display it right there in the toolbar:

Until we get custom IntelliSense, that’s as good as it’s going to get I guess.

TokenStreamRewriter

As of next release, every single modification to the code is done using Antlr4‘s TokenStreamRewriter – which means we’re no longer rewriting strings and using the VBIDE API to rewrite VBA code (which means a TON of code has just gone “poof!”): we now work with the very tokens that the Antlr-generated parser itself works with. This also means we can now make all the changes we want in a given module, and apply the changes all at once – by rewriting the entire module in one go. This means the VBE’s own native undo feature no longer gets overwhelmed with a rename refactoring, and it means fewer parses, too.

There’s a bit of a problem though. There are things our grammar doesn’t handle:

- Line numbers

- Dead code in #If / #Else branches

Rubberduck is kinda cheating, by pre-processing the code such that the parser only sees WS (whitespace) tokens in their place. This worked well… as long as we were using the VBIDE API to rewrite the code. So there’s this part still left to work out: we need the parser’s token stream to determine the “new contents” of a module, but the tokens in there aren’t necessarily the code you had in the VBE before the parse was initiated… and that’s quite a critical issue that needs to be addressed before we can think of releasing.

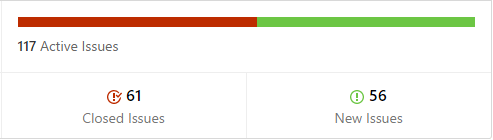

So we’re not releasing just yet. But when we do, it’s likely not going to be v2.0.14, for everything described above: we’re looking at v2.1 stuff here, and that makes me itch to complete the add/remove project references dialog… and then there’s data-driven testing that’s scheduled for 2.1.x…

To be continued…