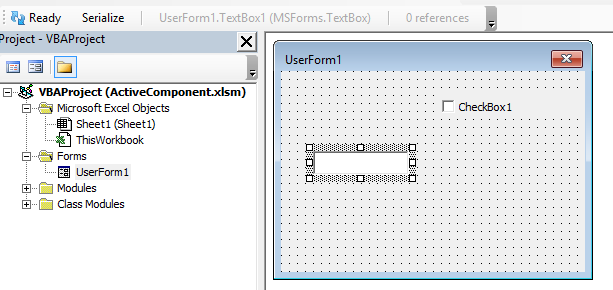

I’ve seen these tutorials. You’ve probably seen them too. They all go “see how easy it is?!” when they end with a glorious UserForm1.Show without explaining anything about what it means for your code and your understanding of programming concepts, to use a form’s default instance like this. Most don’t even venture into explaining anything about that default instance – and off you go, see you on Stack Overflow.

Because if you don’t know what you’re doing, all you’ve learned is how to write code that, in the name of “hey look it’s so easy”, abstracts away crucially important concepts that will, sooner or later, come back to bite you in the …rear end.

What’s that default instance anyway?

A UserForm is essentially a class module with a designer and a VB_PredeclaredId attribute. That PredeclaredId means VBA is automatically creating a global-scope instance of the class, named after that class. If the default instance is ever unloaded or set to Nothing, its internal state gets reset, and automatically reinitialized as soon as the default instance is invoked again. You can Set UserForm1 = Nothing all you want, you can never verify whether UserForm1 Is Nothing, because that expression will always evaluate to False. A default instance is nice for, say, exposing a factory method. But please, please don’t Show the default instance.

Doing. It. Wrong.™

There are a number of red flags invariably raised in many UserForm tutorials:

Unload Me, or worse,Unload UserForm1, in the form’s code-behind. The former makes the form instance a self-destructing object, the latterdestroysresets the default instance, and that’s not necessarily the executing instance – and that leads to all kinds of funky unexpected behavior, and embarrassing duplicate questions on Stack Overflow. Every day.UserForm1.Showat the call site, whereUserForm1isn’t a local variable but the “hey look it’s free” default instance, which means you’re using an object without even realizing it (at least withoutNew-ing it up yourself) – and you’re storing state that belongs to a global instance, which means you’re using an object but without the benefits of object-oriented programming. It also means that…- The application logic is implemented in the form’s code-behind. In programming this [anti-]pattern has a name: the “smart UI”. If a dialog does anything beyond displaying and collecting data, it’s doing someone else’s job. That piece of logic is now coupled with the UI, and it’s impossible to write a unit test for it. It also means you can’t possibly reuse that form for something else in the same project (heck, or for something similar in another project) without making considerable changes to the form’s code-behind. A form that’s used in 20 places and runs the show for 20 functionalities, can’t possibly be anything other than a spaghetti mess.

So that’s what not to do. Flipside.

Doing it right.

What you want at the call site is to show an instance of the form, let the user do its thing, and when the dialog closes, the calling code pulls the data from the form’s state. This means you can’t afford a self-destructing form that wipes out its entire state before the [Ok] button’s Click handler even returns.

Hide it, don’t Unload it.

In .NET’s Windows Forms UI framework (WinForms / the .NET successor of MSForms), a form’s Show method is a function that returns a DialogResult enum value, a bit like a MsgBox does. Makes sense; that Show method tells its caller what the user meant to do with the form’s state: Ok being your green light to process it, Cancel meaning the user chose not to proceed – and your program is supposed to act accordingly.

You see Show-ing a dialog isn’t some fire-and-forget business: if the caller is going to be responsible for knowing what to do when the form is okayed or cancelled, then it’s going to need to know whether the form is okayed or cancelled.

And a form can’t tell its caller anything if clicking the [Ok] button nukes the form object.

The basic code-behind for a form with an [Ok] and a [Cancel] button could look like this:

Option Explicit

'@Folder("UI")

Private cancelled As Boolean

Public Property Get IsCancelled() As Boolean

IsCancelled = cancelled

End Property

Private Sub OkButton_Click()

Hide

End Sub

Private Sub CancelButton_Click()

OnCancel

End Sub

Private Sub UserForm_QueryClose(Cancel As Integer, CloseMode As Integer)

If CloseMode = VbQueryClose.vbFormControlMenu Then

Cancel = True

OnCancel

End If

End Sub

Private Sub OnCancel()

cancelled = True

Hide

End Sub

Notice there are two ways to cancel the dialog: the [Cancel] button, and the [X] button, which would also nuke the object instance if Cancel = True wasn’t specified in the QueryClose handler. Handling QueryClose is fundamental – not doing it means even if you’re not Unload-ing it anywhere, [X]-ing out of the form will inevitably cause issues, because the calling code has all rights to not be expecting a self-destructing object – you need to have the form’s object reference around, for the caller to be able to verify if the form was cancelled when .Show returns.

The calling code looks like this:

With New UserForm1

.Show

If Not .IsCancelled Then

'...

End If

End With

Notice there’s no need to declare a local variable; the With New syntax yields the object reference to the With block, which properly destroys the object whenever the With block is exited – hence why GoTo-jumping out and then back into a With block is never a good idea; this can happen accidentally, with a Resume or Resume Next instruction in an error-handling subroutine.

The Model

A dialog displays and collects data. If the caller needs to know about a UserName and a Password, it doesn’t need to care about some userNameBox and passwordBox textbox controls: what it cares about, is the UserName and the Password that the user provided in these controls – the controls themselves, the ability to hide them, move them, resize them, change their font and border style, etc., is utterly irrelevant. The calling code doesn’t need controls, it needs a model that encapsulates the form’s data.

In its simplest form, the model can take the shape of a few Property Get members in the form’s code-behind:

Public Property Get UserName() As String

UserName = userNameBox.Text

End Property

Public Property Get Password() As String

Password = passwordBox.Text

End Property

Or better, it could be a full-fledged class, exposing Property Get and Property Let members for every property.

The calling code can now get the form’s data without needing to care about controls and knowing that the UserName was entered in a TextBox control, or knowing the Password without knowing that the PasswordChar for the passwordBox was set to *.

Except, it can – form controls are basically public instance fields on the form object: the caller can happily access them at will… and this makes the UserName and Password interesting properties kind of lost in a sea of MSForms boilerplate in IntelliSense. So you implement the model in its own class module instead, and use composition to encapsulate it:

Private viewModel As LoginDialogModel

Public Property Get Model() As LoginDialogModel

Set Model = viewModel

End Property

Public Property Set Model(ByVal value As LoginDialogModel)

Set viewModel = value

End Property

The model could be updated by the textboxes – it could even expose Boolean properties that can be used to enable/disable the [Ok] button, or show/hide a validation error icon:

Private Sub userNameBox_Change()

viewModel.UserName = userNameBox.Text

ValidateForm

End Sub

Private Sub passwordBox_Change()

viewModel.Password = passwordBox.Text

ValidateForm

End Sub

Private Sub ValidateForm()

okButton.Enabled = viewModel.IsValidModel

userNameValidationErrorIcon.Visible = viewModel.IsInvalidUserName

passwordValidationErrorIcon.Visible = viewModel.IsInvalidPassword

End Sub

Now, a problem remains: the caller doesn’t want to see the form’s controls.

The View

So we have a model abstraction that the view can consume, but we don’t have an abstraction for the view. That should be simple enough – let’s add a new class module and define a general-purpose IView interface:

Option Explicit

'@Folder("Abstractions")

'@Interface

Public Function ShowDialog(ByVal viewModel As Object) As Boolean

End Function

Now the form can implement that interface – and because the interface is exposing that ShowDialog method, we don’t need a public IsCancelled property anymore. I’m introducing a Private Type at this point, because I like having only one private field:

Option Explicit

Implements IView

'@Folder("UI")

Private Type TView

IsCancelled As Boolean

Model As LoginDialogModel

End Type

Private this As TView

Private Sub OkButton_Click()

Hide

End Sub

Private Sub CancelButton_Click()

OnCancel

End Sub

Private Sub UserForm_QueryClose(Cancel As Integer, CloseMode As Integer)

If CloseMode = VbQueryClose.vbFormControlMenu Then

Cancel = True

OnCancel

End If

End Sub

Private Sub OnCancel()

this.IsCancelled = True

Hide

End Sub

Private Function IView_ShowDialog(ByVal viewModel As Object) As Boolean

Set this.Model = viewModel

Show

IView_ShowDialog = Not cancelled

End Function

The interface can’t be general-purpose if the Model property is of a type more specific than Object, but it doesn’t matter: the code-behind gets IntelliSense and early-bound, compile-time validation of member calls against it because the Private viewModel field is an implementation detail, and this particular IView implementation is a “login dialog” with a LoginDialogModel; the interface doesn’t need to know, only the implementation.

The [Ok] button will only ever be enabled if the model is valid – that’s one less thing for the caller to worry about, and the logic addressing that concern is neatly encapsulated in the model class itself.

The calling code is supplying the model, so its type is known to the caller – in fact that Property Get member is just provided as a convenience, because it makes little sense to Set a property without being able to Get it later.

Speaking of the calling code, with the addition of a Self property to the model class (Set Self = Me), it could look like this now:

Public Sub Test()

Dim view As IView

Set view = New LoginForm

With New LoginDialogModel

If Not view.ShowDialog(.Self) Then Exit Sub

'consume the model:

Debug.Print .UserName, .Password

End With 'model goes out of scope

End Sub 'view goes out of scope

If you read the previous article about writing unit-testable code, you’re now realizing (if you haven’t already) that this IView interface could be implemented by some MockLoginDialog class that implements ShowDialog by returning a test-configured value, and unit tests could be written against any code that consumes an IView rather than an actual LoginForm, so long as you’ve written it in such a way that it’s the calling code that’s responsible for knowing what specific IView implementation the code is going to be interacting with.

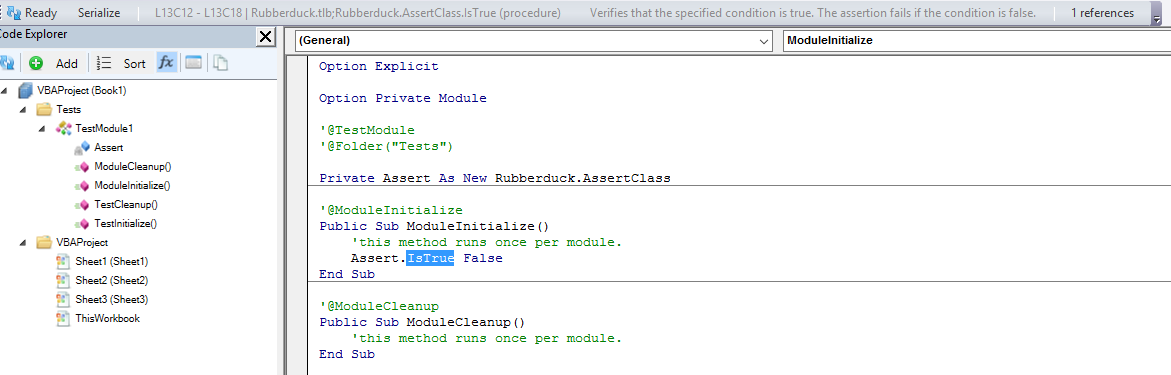

The model’s validation logic could be unit-tested, too:

Const value As String = "1234"

With New LoginDialogModel

.Password = value

Assert.IsTrue .IsInvalidPassword, "'" & value & "' should be invalid."

End With

With a Model and a View, you’re one step away from implementing the New-ing-up a Presenter class, an abstraction that completes the MVP pattern, a much more robust way to write UI-involving code than a Smart UI is.