Creating objects is something we do all the time. When we Set foo = New Something, we create a new instance of the Something class and assign that object reference to the foo variable, which would have been declared locally with Dim foo As Something.

With New

Often, you wish to instantiate Something with initial values for its properties – might look like this:

Dim foo As Something

Set foo = New Something

With foo

.Bar = 42

.Ducky = "Quack"

'...

End With

Or, you could be fancy and make Something have a Self property that returns, well, the instance itself, like this:

Public Property Get Self() As Something

Set Self = Me

End Property

But why would we do that? Because then we can leverage the rather elegant With New syntax:

Dim foo As Something

With New Something

.Bar = 42

.Ducky = "Quack"

'...

Set foo = .Self

End With

The benefits are perhaps more apparent with a factory method:

Public Function NewSomething(ByVal initialBar As Long, ByVal initialDucky As String) As Something

With New Something

.Bar = initialBar

.Ducky = initialDucky

Set NewSomething = .Self

End With

End Function

See, no local variable is needed here, the With block holds the object reference. If we weren’t passing that reference down the call stack by returning it to the caller, the End With would have terminated that object. Not everybody knows that a With block can own an object reference like this, using With New. Without the Self property, a local variable would be needed in order to be able to assign the return value, because a With block doesn’t provide a handle to the object reference it’s holding.

Now the calling code can do this:

Dim foo As Something Set foo = Factories.NewSomething(42, "Quack")

Here the NewSomething function is located in a standard module (.bas) named Factories. The code would have also been legal without qualifying NewSomething with the module name, but if someone is maintaining that code without Rubberduck to tell them by merely clicking on the identifier, meh, too bad for them they’ll have to Shift+F2 (go to definition) on NewSomething and waste time and break their momentum navigating to the Factories module it’s defined in – or worse, looking it up in the Object Browser (F2).

Where to put it?

In other languages, objects can be created with a constructor. In VBA you can’t have that, so you use a factory method instead. Factories manufacture objects, they create things.

In my opinion, the single best place to put a factory method isn’t in a standard/procedural module though – it’s on the class itself. I want my calling code to look something like this:

Dim foo As Something Set foo = Something.Create(42, "Quack")

Last thing I want is some “factory module” that exposes a method for creating instances of every class in my project. But how can we do this? The Create method can’t be invoked without an instance of the Something class, right? But what’s happening here, is that the instance is being automatically created by VBA; that instance is named after the class itself, and there’s a VB_Attribute in the class header that you need to tweak to activate it:

VERSION 1.0 CLASS BEGIN MultiUse = -1 'True END Attribute VB_Name = "Something" '#FunFact controlled by the "Name" property of the class module Attribute VB_GlobalNameSpace = False '#FunFact VBA ignores this attribute Attribute VB_Creatable = False '#FunFact VBA ignores this attribute Attribute VB_PredeclaredId = True '<~ HERE! Attribute VB_Exposed = False '#FunFact controlled by the "Instancing" property of the class module

The attribute is VB_PredeclaredId, which is False by default. At a low level, each object instance has an ID; by toggling this attribute value, you tell VBA to pre-declare that ID… and that’s how you get what’s essentially a global-scope free-for-all instance of your object.

That can be a good thing… but as is often the case with forms (which also have a predeclared ID), storing state in that instance leads to needless bugs and complications.

Interfaces

The real problem is that we really have two interfaces here, and one of them (the factory) shouldn’t be able to access instance data… but it needs to be able to access the properties of the object it’s creating!

If only there was a way for a VBA class to present one interface to the outside world, and another to the Create factory method!

VERSION 1.0 CLASS BEGIN MultiUse = -1 'True END Attribute VB_Name = "ISomething" Attribute VB_GlobalNameSpace = False Attribute VB_Creatable = False Attribute VB_PredeclaredId = False Attribute VB_Exposed = False Option Explicit Public Property Get Bar() As Long End Property Public Property Get Ducky() As String End Property

This would be some ISomething class: an interface that the Something class will implement.

The Something class would look like this- Notice that it only exposes Property Get accessors, and that the Create method returns the object through the ISomething interface:

VERSION 1.0 CLASS

BEGIN

MultiUse = -1 'True

END

Attribute VB_Name = "Something"

Attribute VB_GlobalNameSpace = False

Attribute VB_Creatable = False

Attribute VB_PredeclaredId = True

Attribute VB_Exposed = False

Option Explicit

Private Type TSomething

Bar As Long

Ducky As String

End Type

Private this As TSomething

Implements ISomething

Public Function Create(ByVal initialBar As Long, ByVal initialDucky As String) As ISomething

With New Something

.Bar = initialBar

.Ducky = initialDucky

Set Create = .Self

End With

End Function

Public Property Get Self() As ISomething

Set Self = Me

End Property

Public Property Get Bar() As Long

Bar = this.Bar

End Property

Friend Property Let Bar(ByVal value As Long)

this.Bar = value

End Property

Public Property Get Ducky() As String

Ducky = this.Ducky

End Property

Friend Property Let Ducky(ByVal value As String)

this.Ducky = value

End Property

Private Property Get ISomething_Bar() As Long

ISomething_Bar = Bar

End Property

Private Property Get ISomething_Ducky() As String

ISomething_Ducky = Ducky

End Property

The Friend properties would only be accessible within that project; if that’s not a concern then they could also be Public, doesn’t really matter – the calling code only really cares about the ISomething interface:

With Something.Create(42, "Quack")

Debug.Print .Bar 'prints 42

.Bar = 42 'illegal, member not on interface

End With

Here the calling scope is still tightly coupled with the Something class though. But if we had a factory interface…

VERSION 1.0 CLASS BEGIN MultiUse = -1 'True END Attribute VB_Name = "ISomethingFactory" Attribute VB_GlobalNameSpace = False Attribute VB_Creatable = False Attribute VB_PredeclaredId = False Attribute VB_Exposed = False Option Explicit Public Function Create(ByVal initialBar As Long, ByVal initialDuck As String) As ISomething End Function

…and made Something implement that interface…

Implements ISomething

Implements ISomethingFactory

Public Function Create(ByVal initialBar As Long, ByVal initialDucky As String) As ISomething

With New Something

.Bar = initialBar

.Ducky = initialDucky

Set Create = .Self

End With

End Function

Private Function ISomethingFactory_Create(ByVal initialBar As Long, ByVal initialDucky As String) As ISomething

Set ISomethingFactory_Create = Create(initialBar, initialDucky)

End Function

…now we basically have an abstract factory that we can pass around to everything that needs to create an instance of Something or, even cooler, of anything that implements the ISomething interface:

Option Explicit

Public Sub Main()

Dim factory As ISomethingFactory

Set factory = Something.Self

With MyMacro.Create(factory)

.Run

End With

End Sub

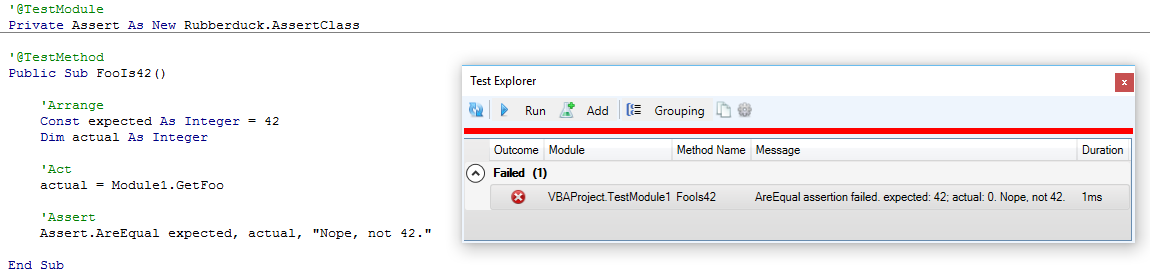

Of course this is a contrived example. Imagine Something is rather some SqlDataService encapsulating some ADODB data access, and suddenly it’s possible to execute MyMacro.Run without hitting a database at all, by implementing the ISomething and ISomethingFactory interfaces in some FakeDataService class that unit tests can use to test-drive the logic without ever needing to hit a database.

A factory is a creational pattern that allows us to parameterize the creation of an object, and even abstract away the very concept of creating an instance of an object, so much that the concrete implementation we’re actually coding against, has no importance anymore – all that matters is the interface we’re using.

Using interfaces, we can segregate parts of our API into different “views” of the same object and, benefiting from coding conventions, achieve get-only properties that can only be assigned when the object is initialized by a factory method.

If you really want to work with a specific implementation, you can always couple your code with a specific Something – but if you stick to coding against interfaces, you’ll find that writing unit tests to validate your logic without testing your database connections, the SQL queries, the presence of the data in the database, the network connectivity, and all the other things that can go wrong, that you have no control over, and that you don’t need to cover in a unit test, …will be much easier.

The whole setup likely isn’t a necessity everywhere, but abstract factories, factory methods, and interfaces, remain useful tools that are good to have in one’s arsenal… and Rubberduck will eventually provide tooling to generate all that boilerplate code.

Sounds like fun? Help us do it!