I have recently written (100% VBA) a proof-of-concept for a Model-View-ViewModel (MVVM) framework, and since the prototype works exactly as needed (with some rough edges of course)… I’ve decided to explore what Rubberduck can do to make MVVM fully supported, but going down that path poses a serious problem that needs a very good and well thought-out solution.

A Vision of a Framework

When you start a new project in Visual Studio (including 6.0 /VB6), the IDE prompts for a project type, essentially asking “what are we building today?“

In VBA the assumption is that you just want to write a bit of script to automate some document manipulation. And then the framework so to speak, is the VBA Standard Library: functions, methods, constants, and actual objects too; all globally-scoped for convenience and quick-and-easy access: a fully spelled-out VBA.Interaction.MsgBox function call is a rare sight! Combined with the nonexistence of namespaces, the flip side is that the global scope is easily polluted, and name collisions are inevitable since anything exposed by any library becomes globally accessible. This makes fully-qualified global function calls appear sporadically sprinkled in the code, which can be confusing. I digress, but what I mean to get at is that this is part of what made Microsoft make the shift to the .NET platform in the early 2000’s, and eventually abandon the Visual Basic Editor to its fate. The COM platform and Win32 API was the framework, and Win32 programming languages built on top of that.

This leaves two approaches for a vision of a “framework” for VBA:

- Package a type library and ship it.

- Pros: any COM-visible library will work, can be written in .NET

- Cons: projects now have a hard dependency on a specific type library; updating is a mess, etc.

- Embed the framework into VBA projects, pretty much like JavaScript does.

- Pros: devs are in charge of everything, framework is 100% VBA and inherently open-source, updating is essentially seamless for any non-breaking change, no early-bound dependencies, graceful late-bound degradation, etc.

- Cons: VBA devs and maintainers that aren’t using Rubberduck will be massively lost in the source code (framework would cleanly leverage @Folder annotations), but then when the host application allows it this could be mitigated by embedding the code into its own separate VBA project and reference it from other projects (e.g. ship an Excel add-in with the framework code your VBA project depends on).

I think I’m slightly biased here, but I think this rules out the type library approach regardless. So we need a way to make this work in VBA, with VBA source code that lives in a GitHub repository with vetted, trusted content.

Where Rubberduck fits in

Like Visual Studio, Rubberduck could prompt VBA devs with “what are we building today?” and offer to pull various “bundles” of modules from this GitHub repository into the active project. Rubberduck would request the available “bundles” from api.rubberduckvba.com, which would return with “bundle metadata” describing each “package” (is “nugget” forbidden to use as a name for these / play on “nuget” (the package manager for .NET)?), and then list them in a nice little dialog.

The “nugget” metadata would include a name, a description, and the path to each file to download for it. Every package would be the same “version”, but the tool could easily request any particular “tag” or “release” version, and/or pull from “main” or from “next” branches, and the source code / framework itself could then easily be a collaborative effort, with its own features and projects and milestones and collaborators, completely separate from the C# Rubberduck code base.

This complete decoupling from Rubberduck means you don’t need to use Rubberduck to leverage this VBA code in your VBA projects, and new tags / “releases” would be entirely independent of Rubberduck’s own release cycles. That means you’re using, say, future-Rubberduck 2.7.4 and the “nuggets” feature offers “v1.0 [main]” and “v1.1 [next]”; one day you’re still using Rubberduck 2.7.4 but now you get “v1.1 [main]”, “v1.0”, and “v1.2 [next]” to chose from, and if you updated the “nuggets” in your project from v1.0 to v1.1 then Rubberduck inspections would flag uses of any obsolete members that would now be decorated with @Obsolete annotations… it’s almost like this annotation was presciently made for this.

But before we can even think of implementing something like this and make MVVM infrastructure the very first “nugget”, we need a rock-solid framework in the first place.

Unit Tests

I had already written the prototype in a highly decoupled manner, mindful of dependencies and how things could later be tested from the outside. I’m very much not-a-zealot when it comes to things like Test-Driven Development (TDD), but I do firmly believe unit tests provide a solid safety net and documentation for everything that matters – especially if the project is to make any kind of framework, where things need to provably work.

And then it makes a wonderful opportunity to blog about writing unit tests with Rubberduck, something I really haven’t written nearly enough about.

Tests? Why?!

Just by writing these tests, I’ve found and fixed edge-case bugs and improved decoupling and cohesion by extracting (and naming!) smaller chunks of functionality into their own separate class module. The result is quite objectively better, simpler code.

Last but not least, writing testable code (let alone the tests!) in VBA makes a great way to learn these more advanced notions and concepts in a language you’re already familiar with.

If you’re new to VBA and programming in general, or if you’re not a programmer and you’re only interested in making macros, then reading any further may make your head spin a bit (if that’s already under way… I’m sorry!), so don’t hesitate to ask here or on the examples repository on GitHub if you have any questions! This article is covering a rather advanced topic, beyond classes and interfaces, but keep in mind that unit testing does not require OOP! It just so happens that object-oriented code adhering to SOLID principles tends to be easily testable.

This is an ongoing project and I’m still working on the test suite and refactoring things; I wouldn’t want to upload the code to GitHub in its current shape, so I’ll come back here with a link once I have something that’s relatively complete.

Where to Start?

There’s a relatively small but very critical piece of functionality that makes a good place to begin in the MVVM infrastructure code (see previous article): the BindingPath class, which I’ve pulled out of PropertyBinding this week. The (still too large for its own good) PropertyBinding class is no longer concerned with the intricacies of resolving property names and values: both this.Source and this.Target are declared As IBindingPath in a PropertyBinding now, which feels exactly right.

The purpose of a BindingPath is to take a “binding context” object and a “binding path” string (the binding path is always relative to the binding context), and to resolve the member call represented there. For example, this would be a valid use of the class:

Dim Path As IBindingPath

Set Path = BindingPath.Create(Sheet1.Shapes("Shape1").TextFrame.Characters, "Text")

This Path object implements TryReadPropertyValue and TryWritePropertyValue methods that the BindingManager can invoke as needed.

'@Folder MVVM.Infrastructure.Bindings

'@ModuleDescription "An object that can resolve a string property path to a value."

'@PredeclaredId

Option Explicit

Implements IBindingPath

Private Type TState

Context As Object

Path As String

Object As Object

PropertyName As String

End Type

Private This As TState

'@Description "Creates a new binding path from the specified property path string and binding context."

Public Function Create(ByVal Context As Object, ByVal Path As String) As IBindingPath

GuardClauses.GuardNonDefaultInstance Me, BindingPath, TypeName(Me)

GuardClauses.GuardNullReference Context, TypeName(Me)

GuardClauses.GuardEmptyString Path, TypeName(Me)

Dim Result As BindingPath

Set Result = New BindingPath

Set Result.Context = Context

Result.Path = Path

Result.Resolve

Set Create = Result

End Function

'@Description "Gets/Sets the binding context."

Public Property Get Context() As Object

Set Context = This.Context

End Property

Public Property Set Context(ByVal RHS As Object)

GuardClauses.GuardDefaultInstance Me, BindingPath, TypeName(Me)

GuardClauses.GuardNullReference RHS, TypeName(Me)

GuardClauses.GuardDoubleInitialization This.Context, TypeName(Me)

Set This.Context = RHS

End Property

'@Description "Gets/Sets a string representing a property path against the binding context."

Public Property Get Path() As String

Path = This.Path

End Property

Public Property Let Path(ByVal RHS As String)

GuardClauses.GuardDefaultInstance Me, BindingPath, TypeName(Me)

GuardClauses.GuardEmptyString RHS, TypeName(Me)

GuardClauses.GuardDoubleInitialization This.Path, TypeName(Me)

This.Path = RHS

End Property

'@Description "Gets the bound object reference."

Public Property Get Object() As Object

Set Object = This.Object

End Property

'@Description "Gets the name of the bound property."

Public Property Get PropertyName() As String

PropertyName = This.PropertyName

End Property

'@Description "Resolves the Path to a bound object and property."

Public Sub Resolve()

This.PropertyName = ResolvePropertyName(This.Path)

Set This.Object = ResolvePropertyPath(This.Context, This.Path)

End Sub

Private Function ResolvePropertyName(ByVal PropertyPath As String) As String

Dim Parts As Variant

Parts = Strings.Split(PropertyPath, ".")

ResolvePropertyName = Parts(UBound(Parts))

End Function

Private Function ResolvePropertyPath(ByVal Context As Object, ByVal PropertyPath As String) As Object

Dim Parts As Variant

Parts = Strings.Split(PropertyPath, ".")

If UBound(Parts) = LBound(Parts) Then

Set ResolvePropertyPath = Context

Else

Dim RecursiveProperty As Object

Set RecursiveProperty = CallByName(Context, Parts(0), VbGet)

If RecursiveProperty Is Nothing Then Exit Function

Set ResolvePropertyPath = ResolvePropertyPath(RecursiveProperty, Right$(PropertyPath, Len(PropertyPath) - Len(Parts(0)) - 1))

End If

End Function

Private Property Get IBindingPath_Context() As Object

Set IBindingPath_Context = This.Context

End Property

Private Property Get IBindingPath_Path() As String

IBindingPath_Path = This.Path

End Property

Private Property Get IBindingPath_Object() As Object

Set IBindingPath_Object = This.Object

End Property

Private Property Get IBindingPath_PropertyName() As String

IBindingPath_PropertyName = This.PropertyName

End Property

Private Sub IBindingPath_Resolve()

Resolve

End Sub

Private Function IBindingPath_ToString() As String

IBindingPath_ToString = StringBuilder _

.AppendFormat("Context: {0}; Path: {1}", TypeName(This.Context), This.Path) _

.ToString

End Function

Private Function IBindingPath_TryReadPropertyValue(ByRef outValue As Variant) As Boolean

If This.Object Is Nothing Then Resolve

On Error Resume Next

outValue = VBA.Interaction.CallByName(This.Object, This.PropertyName, VbGet)

IBindingPath_TryReadPropertyValue = (Err.Number = 0)

On Error GoTo 0

End Function

Private Function IBindingPath_TryWritePropertyValue(ByVal Value As Variant) As Boolean

If This.Object Is Nothing Then Resolve

On Error Resume Next

VBA.Interaction.CallByName This.Object, This.PropertyName, VbLet, Value

IBindingPath_TryWritePropertyValue = (Err.Number = 0)

On Error GoTo 0

End Function

Here’s our complete “system under test” (SUT) as far as the BindingPathTests module goes. We have a Create factory method, Context and Path properties, just like the class we’re testing.

The path object is itself read-only once initialized, but the binding source may resolve to Nothing or to a different object reference over the course of the object’s lifetime: say we want a binding path to SomeViewModel.SomeObjectProperty; when we first create the binding, SomeObjectProperty might very well be Nothing, and then it’s later Set-assigned to a valid object reference. This is why the IBindingPath interface needs to expose a Resolve method, so that IPropertyBinding can invoke it as needed, as the binding is being applied.

We’ll want a test for every guard clause, and each method needs at least one test as well.

So, I’m going to add a new test module and call it BindingPathTests. Rubberduck’s templates are good-enough to depict the mechanics and how things work at a high level, but if you stick to the templates you’ll quickly find your unit tests rather boring, wordy, and repetitive: we must break out of the mold, there isn’t one true way to do this!

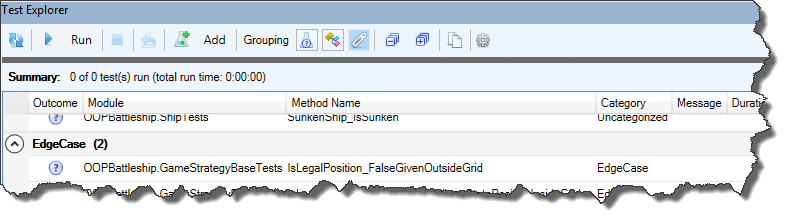

Rubberduck discovers unit tests in standard modules annotated with @TestModule. Test methods are any [parameterless, for now] method annotated with a @TestMethod annotation that can have a category string – the Test Explorer can group your tests using these categories. The declarations section of a test module must include a declaration (early or late bound) for an Rubberduck.AssertClass or Rubberduck.PermissiveAssertClass (both implement the same internal interface; the “permissive” one has VBA-like equality semantics, and the default one has stricter type equality requirements (a Long can’t be equal to a Double, for example). The default test template also defines a FakesProvider object, but we’re not going to need it now (if we needed to test logic that involved e.g. branching on the result of a MsgBox function call, we could hook into the MsgBox function and configure it to return what the test needs it to return, which is honestly wicked awesome). So our test module might look something like this at first:

'@Folder Tests.Bindings

'@TestModule

Option Explicit

Option Private Module

#Const LateBind = LateBindTests

#If LateBind Then

Private Assert As Object

#Else

Private Assert As Rubberduck.AssertClass

#End If

With this conditionally-compiled setup, all we need to toggle between late and early binding is to define a project-scoped conditional compilation argument: bring up the project properties and type LateBindTests=0 or LateBindTests=1 in that box, and just like that you can control conditional compilation project-wide without modifying a single module.

The first thing to do is to get the test state defined, and implement TestInitialize and TestCleanup methods that configure this state – in the case of BindingManagerTests, I’m going to add a private type and a private field to define and hold the current test state:

Private Type TState

ExpectedErrNumber As Long

ExpectedErrSource As String

ExpectedErrorCaught As Boolean

ConcreteSUT As BindingManager

AbstractSUT As IBindingManager

HandlePropertyChangedSUT As IHandlePropertyChanged

BindingSource As TestBindingObject

BindingTarget As TestBindingObject

SourcePropertyPath As String

TargetPropertyPath As String

Command As TestCommand

End Type

Private Test As TState

Unit Testing Paradigm

Test modules are special, in the sense that they aren’t (absolutely shouldn’t be anyway) accessible from any code path in the project. Rubberduck invokes them one by one when you run a command like “run all tests” or “repeat last run”. But there’s a little more to it than that, worthy of mention.

VBA being single-threaded, tests are invoked by Rubberduck on the UI/main thread, and uses a bit of trickery to keep its own UI somewhat responsive. Each module runs sequentially, and each test inside each module runs sequentially as well – but the test execution order still shouldn’t be considered deterministic, and each test should be completely independent of every other test, such that executing all tests in any given order always produces the same outcomes.

A test that makes no assertions will be green/successful. When writing unit tests, the first thing you want to see is a test that’s failing (you can’t trust a test you have never seen fail!), and with Rubberduck in order to give a test a reason to fail, you use Assert methods (wiki).

When Rubberduck begins processing a test module, it invokes the methods (again, sequentially but not in an order that should matter) marked @ModuleInitialize in the module – ideally that would be only one method.

This is where the Assert object should be assigned (the default test templates do this):

'@ModuleInitialize

Private Sub ModuleInitialize()

#If LateBind Then

'requires HKCU registration of the Rubberduck COM library.

Set Assert = CreateObject("Rubberduck.PermissiveAssertClass")

#Else

'requires project reference to the Rubberduck COM library.

Set Assert = New Rubberduck.PermissiveAssertClass

#End If

End Sub

Rubberduck’s test engine will then execute all methods (usually cleaner with only one though) annotated with @TestInitialize before executing each test in the module; that is the best place to put the wordy setup code that would otherwise need to be in pretty much every single test of the module:

'@TestInitialize

Private Sub TestInitialize()

Dim Context As TestBindingObject

Set Context = New TestBindingObject

Set Context.TestBindingObjectProperty = New TestBindingObject

Test.Path = "TestBindingObjectProperty.TestStringProperty"

Test.PropertyName = "TestStringProperty"

Set Test.BindingSource = Context.TestBindingObjectProperty

Set Test.BindingContext = Context

Set Test.ConcreteSUT = BindingPath.Create(Test.BindingContext, Test.Path)

Set Test.AbstractSUT = Test.ConcreteSUT

End Sub

By moving the test state to module level rather than having it local to each test, we already eliminate a lot of code duplication, and the Test module variable makes a rather nifty way to access the current test state, too!

Methods annotated with @TestCleanup are automatically invoked after each test in the module; in order to avoid accidentally sharing state between tests, every object reference should be explicitly set to Nothing, and values of intrinsic data types should be explicitly reset to their respective default value:

'@TestCleanup

Private Sub TestCleanup()

Set Test.ConcreteSUT = Nothing

Set Test.AbstractSUT = Nothing

Set Test.BindingSource = Nothing

Set Test.BindingContext = Nothing

Test.Path = vbNullString

Test.PropertyName = vbNullString

Test.ExpectedErrNumber = 0

Test.ExpectedErrSource = vbNullString

Test.ExpectedErrorCaught = False

End Sub

What Goes Into the Test State?

A number of members should always be in the Test state structure:

ConcreteSUT (or just SUT) and AbstractSUT both point to the same object, through the default interface (BindingPath) and the explicit one (IBindingPath), respectively.- If the system under test class implements additional interfaces, having a pointer to the SUT object with these interfaces is also useful. For example the

TState type for the BindingManager class has a HandlePropertyChangedSUT As IHandlePropertyChanged member, because the class implements this interface. - Default property values and dependency setup: we want a basic default SUT configured and ready to be tested (or fine-tuned and then tested).

ExpectedErrNumber, ExpectedErrSource, and ExpectedErrorCaught are useful when a test is expecting a given input to produce a particular specific error.

Expecting Errors

The “expected error” test method template works for its purpose, but having this on-error-assert logic duplicated everywhere is rather ugly. Consider pulling that logic into a private method instead (I’m considering adding this into Rubberduck’s test module templates):

Private Sub ExpectError()

Dim Message As String

If Err.Number = Test.ExpectedErrNumber Then

If (Test.ExpectedErrSource = vbNullString) Or (Err.Source = Test.ExpectedErrSource) Then

Test.ExpectedErrorCaught = True

Else

Message = "An error was raised, but not from the expected source. " & _

"Expected: '" & TypeName(Test.ConcreteSUT) & "'; Actual: '" & Err.Source & "'."

End If

ElseIf Err.Number <> 0 Then

Message = "An error was raised, but not with the expected number. Expected: '" & Test.ExpectedErrNumber & "'; Actual: '" & Err.Number & "'."

Else

Message = "No error was raised."

End If

If Not Test.ExpectedErrorCaught Then Assert.Fail Message

End Sub

With this infrastructure in place, the unit tests for all guard clauses in the module can look like this – it’s still effectively doing Arrange-Act-Assert like the test method templates strongly suggest, only implicitly so (each “A” is essentially its own statement, see comments in the tests below):

'@TestMethod("GuardClauses")

Private Sub Create_GuardsNullBindingContext()

Test.ExpectedErrNumber = GuardClauseErrors.ObjectCannotBeNothing '<~ Arrange

On Error Resume Next

BindingPath.Create Nothing, Test.Path '<~ Act

ExpectError '<~ Assert

On Error GoTo 0

End Sub

'@TestMethod("GuardClauses")

Private Sub Create_GuardsEmptyPath()

Test.ExpectedErrNumber = GuardClauseErrors.StringCannotBeEmpty '<~ Arrange

On Error Resume Next

BindingPath.Create Test.BindingContext, vbNullString '<~ Act

ExpectError '<~ Assert

On Error GoTo 0

End Sub

'@TestMethod("GuardClauses")

Private Sub Create_GuardsNonDefaultInstance()

Test.ExpectedErrNumber = GuardClauseErrors.InvalidFromNonDefaultInstance '<~ Arrange

On Error Resume Next

With New BindingPath

.Create Test.BindingContext, Test.Path '<~ Act

ExpectError '<~ Assert

End With

On Error GoTo 0

End Sub

And then similar tests exist for the respective guard clauses of Context and Path members. Having tests that validate that guard clauses are doing their job is great: it tells us exactly how not to use the class… and that doesn’t tell us much about what a BindingPath object actually does.

Testing the Actual Functionality

The methods we’re testing need to be written in a way that makes it possible for a test to determine whether it’s doing its job correctly or not. For functions and properties, the return value is the perfect thing to Assert on. For Sub procedures, you have to Assert on the side-effects, and have verifiable and useful, reliable ways to verify them.

These two tests validate that the BindingPath returned by the Create factory method has resolved the PropertyName and Object properties, respectively.

'@TestMethod("Bindings")

Private Sub Create_ResolvesPropertyName()

Dim SUT As BindingPath

Set SUT = BindingPath.Create(Test.BindingContext, Test.Path)

Assert.IsFalse SUT.PropertyName = vbNullString

End Sub

'@TestMethod("Bindings")

Private Sub Create_ResolvesBindingSource()

Dim SUT As BindingPath

Set SUT = BindingPath.Create(Test.BindingContext, Test.Path)

Assert.IsNotNothing SUT.Object

End Sub

I could have made multiple assertions in a test, like this…

'@TestMethod("Bindings")

Private Sub Create_ResolvesBindingSource()

Dim SUT As BindingPath

Set SUT = BindingPath.Create(Test.BindingContext, Test.Path)

Assert.IsFalse SUT.PropertyName = vbNullString

Assert.IsNotNothing SUT.Object

End Sub

The Test Explorer would say “IsFalse assert failed” or “IsNotNothing assert failed”, so it’s arguably (perhaps pragmatically so) still useful and clear enough why that test would fail (and if you had multiple Assert.IsFalse calls in a test you could provide a different message for each)… but really as a rule of thumb, tests want to have one reason to fail. If the conditions to meaningfully pass or fail a test aren’t present, use Assert.Inconclusive to report the test as such:

'@TestMethod("Bindings")

Private Sub Resolve_SetsBindingSource()

With New BindingPath

.Path = Test.Path

Set .Context = Test.BindingContext

If Not .Object Is Nothing Then Assert.Inconclusive "Object reference is unexpectedly set."

.Resolve

Assert.AreSame Test.BindingSource, .Object

End With

End Sub

'@TestMethod("Bindings")

Private Sub Resolve_SetsBindingPropertyName()

With New BindingPath

.Path = Test.Path

Set .Context = Test.BindingContext

If .PropertyName <> vbNullString Then Assert.Inconclusive "PropertyName is unexpectedly non-empty."

.Resolve

Assert.AreEqual Test.PropertyName, .PropertyName

End With

End Sub

This mechanism is especially useful when the test state isn’t in local scope and there’s a real possibility that the TestInitialize method is eventually modified and inadvertently breaks a test. Such conditional Assert.Inconclusive calls are definitely a form of defensive programming, just like having guard clauses throwing custom meaningful errors.

Note that while we know that the BindingPath.Create function invokes the Resolve method, the tests for Resolve don’t involve Create: the Path and Context are being explicitly spelled out, and the .Resolve method is invoked from a New instance.

And that’s pretty much everything there is to test in the BindingPath class.

There’s one thing I haven’t mentioned yet, that you might have caught in the TState type:

BindingSource As TestBindingObject

BindingTarget As TestBindingObject

This TestBindingObject is a test stub: it’s a dependency of the class (it’s the “binding context” of the test path) and it’s a real object, but it is implemented in a bit of a special way that the BindingPath tests don’t do justice to.

Test Stubs

Eventually Rubberduck’s unit testing framework will feature a COM-visible wrapper around Moq, a popular mocking framework for .NET that Rubberduck already uses for its own unit test requirements. When this happens Rubberduck unit tests will no longer need such “test stubs”. Instead, the framework will generate them at run-time and make them work exactly as specified/configured by a unit test, and “just like that” VBA/VB6 suddenly becomes surprisingly close to being pretty much on par with professional, current-day IDE tooling.

The ITestStub interface simply formalizes the concept:

'@Exposed

'@Folder Tests.Stubs

'@ModuleDescription "An object that stubs an interface for testing purposes."

'@Interface

Option Explicit

'@Description "Gets the number of times the specified member was invoked in the lifetime of the object."

Public Property Get MemberInvokes(ByVal MemberName As String) As Long

End Property

'@Description "Gets a string representation of the object's internal state, for debugging purposes (not intended for asserts!)."

Public Function ToString() As String

End Function

A TestStubBase “base class” provides the common implementation mechanics that every class implementing ITestStub will want to use – the idea is to use a keyed data structure to track the number of times each member is invoked during the lifetime of the object:

'@Folder Tests.Stubs

Option Explicit

Private Type TState

MemberInvokes As Dictionary

End Type

Private This As TState

'@Description "Tracks a new invoke of the specified member."

Public Sub OnInvoke(ByVal MemberName As String)

Dim newValue As Long

If This.MemberInvokes.Exists(MemberName) Then

newValue = This.MemberInvokes.Item(MemberName) + 1

This.MemberInvokes.Remove MemberName

Else

newValue = 1

End If

This.MemberInvokes.Add MemberName, newValue

End Sub

'@Description "Gets the number of invokes made against the specified member in the lifetime of this object."

Public Property Get MemberInvokes(ByVal MemberName As String) As Long

If This.MemberInvokes.Exists(MemberName) Then

MemberInvokes = This.MemberInvokes.Item(MemberName)

Else

MemberInvokes = 0

End If

End Property

'@Description "Gets a string listing the MemberInvokes cache content."

Public Function ToString() As String

Dim MemberNames As Variant

MemberNames = This.MemberInvokes.Keys

With New StringBuilder

Dim i As Long

For i = LBound(MemberNames) To UBound(MemberNames)

Dim Name As String

Name = MemberNames(i)

.AppendFormat "{0} was invoked {1} time(s)", Name, This.MemberInvokes.Item(Name)

Next

ToString = .ToString

End With

End Function

Private Sub Class_Initialize()

Set This.MemberInvokes = New Dictionary

End Sub

With this small bit of infrastructure, the TestBindingObject class is a full-fledged mock object that can increment a counter whenever a member is invoked, and that can be injected as a dependency for anything that needs an IViewModel:

'@Folder Tests.Stubs

'@ModuleDescription "An object that can stub a binding source or target for unit tests."

Option Explicit

Implements ITestStub

Implements IViewModel

Implements INotifyPropertyChanged

Private Type TState

Stub As TestStubBase

Handlers As Collection

TestStringProperty As String

TestNumericProperty As Long

TestBindingObjectProperty As TestBindingObject

Validation As IHandleValidationError

End Type

Private This As TState

Public Property Get TestStringProperty() As String

This.Stub.OnInvoke "TestStringProperty.Get"

TestStringProperty = This.TestStringProperty

End Property

Public Property Let TestStringProperty(ByVal RHS As String)

This.Stub.OnInvoke "TestStringProperty.Let"

If This.TestStringProperty <> RHS Then

This.TestStringProperty = RHS

OnPropertyChanged Me, "TestStringProperty"

End If

End Property

Public Property Get TestNumericProperty() As Long

This.Stub.OnInvoke "TestNumericProperty.Get"

TestNumericProperty = This.TestNumericProperty

End Property

Public Property Let TestNumericProperty(ByVal RHS As Long)

This.Stub.OnInvoke "TestNumericProperty.Let"

If This.TestNumericProperty <> RHS Then

This.TestNumericProperty = RHS

OnPropertyChanged Me, "TestNumericProperty"

End If

End Property

Public Property Get TestBindingObjectProperty() As TestBindingObject

This.Stub.OnInvoke "TestBindingObjectProperty.Get"

Set TestBindingObjectProperty = This.TestBindingObjectProperty

End Property

Public Property Set TestBindingObjectProperty(ByVal RHS As TestBindingObject)

This.Stub.OnInvoke "TestBindingObjectProperty.Set"

If Not This.TestBindingObjectProperty Is RHS Then

Set This.TestBindingObjectProperty = RHS

OnPropertyChanged Me, "TestBindingObjectProperty"

End If

End Property

Private Sub OnPropertyChanged(ByVal Source As Object, ByVal PropertyName As String)

Dim Handler As IHandlePropertyChanged

For Each Handler In This.Handlers

Handler.OnPropertyChanged Source, PropertyName

Next

End Sub

Private Sub Class_Initialize()

Set This.Stub = New TestStubBase

Set This.Handlers = New Collection

Set This.Validation = ValidationManager.Create

End Sub

Private Sub INotifyPropertyChanged_OnPropertyChanged(ByVal Source As Object, ByVal PropertyName As String)

OnPropertyChanged Source, PropertyName

End Sub

Private Sub INotifyPropertyChanged_RegisterHandler(ByVal Handler As IHandlePropertyChanged)

This.Handlers.Add Handler

End Sub

Private Property Get ITestStub_MemberInvokes(ByVal MemberName As String) As Long

ITestStub_MemberInvokes = This.Stub.MemberInvokes(MemberName)

End Property

Private Function ITestStub_ToString() As String

ITestStub_ToString = This.Stub.ToString

End Function

Private Property Get IViewModel_Validation() As IHandleValidationError

Set IViewModel_Validation = This.Validation

End Property

This functionality will be extremely useful when testing the actual property bindings: for example we can assert that a method was invoked exactly once, and fail a test if the method was invoked twice (and/or if it never was).

There’s a lot more to discuss about unit testing in VBA with Rubberduck! I hope this article gives a good idea of how to get the best out of Rubberduck’s unit testing feature.