If you’re a seasoned VBA developer, you probably have your “VBA Toolbox” – a set of classes that you systematically include in pretty much every single new VBA project.

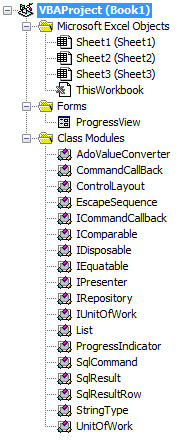

Before you’ve even written a single line of code, your project might look something like this already:

The VBE’s Project Explorer gives you folders that regroup components by component type: forms in a folder, standard modules in another, and classes in another.

That’s great ok for small projects, perhaps. But as your toolbox grows, the classes that are specific to your project get drowned in a sea of class modules, and if you’re into object-oriented programming, you soon end up finding needles in a haystack. “But they’re sorted alphabetically, it’s not that bad!” – sure. And then you come up with all kinds of prefixes and naming schemes to keep related things together, to trick the sorting and actually manage to find things in a decent manner.

The truth is, this sucks.

Now picture this:

You shouldn’t have to care about a component’s type. Since forever, the VBE has forced VBA developers to accept that it could possibly make sense to have completely unrelated forms grouped together, and completely unrelated classes together, just because they’re the same type of VBA objects.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. I like how Visual Studio /.net lets you organize things in folders, which [can] define namespaces, which are a scope on their own.

There’s not really a concept of namespaces inside a VBA project: you could simulate them with standard modules that expose global objects that regroup functionality, but still every component in a project is accessible from anywhere in that project anyway. And who needs namespaces anyway?

Rubberduck 2.0 will not give you namespaces – that would be defying the VBA compiler (you can’t have two classes with the same name in the same project). What it will give you though, is folders.

Cool! How does it work?

Since the early versions of Rubberduck, we’ve been using @annotations (aka “magic comments”) in the unit testing feature, to identify test modules and test methods. Rubberduck 2.0 simply expands on this, so you can annotate a module like this:

'@Folder Foo.Bar

And that module will be shown under a “Bar” folder, itself under a “Foo” folder. How simple is that! We’ll eventually make the delimiter configurable too, so if you prefer this:

'@Folder Foo/Bar

Then you can have it!

With the ability to easily organize your modules into a “virtual folder hierarchy”, adhering to the Single Responsibility Principle and writing object-oriented code that implies many small specialized classes, is no longer going to clutter up your IDE… now be kind, give your colleagues a link to Rubberduck’s website 😉

The Code Explorer

The goal behind the Code Explorer feature, is to make it easier to navigate your VBA project. It’s not just about organizing your code with folders: since version 1.21, the Code Explorer has allowed VBA devs to drill down and explore a module’s members without even looking at the code:

The 2.0 Code Explorer is still under development – but it’s coming along nicely. If you’re using the latest release (v1.4.3), you’ll notice that this treeview has something different: next release every dockable toolwindow will be an embedded WPF/XAML user control, which means better layouts, and an altogether nicer-looking UI. This change isn’t being done just because it’s prettier: it was pretty much required, due to massive architectural changes.

Stay tuned!