The accompanying code for this article is here on GitHub.

Factory Pattern

A factory is exactly what it sounds like: it’s an object whose role is to make things; it encapsulates the notion of creating an object.

Dim thing As Something

Set thing = New Something '<~ type is known at compile-time

Dim lateBoundThing As Object

Set lateBoundThing = CreateObject("Some.ProgID") '<~ Windows Registry lookup at run-time

Whenever we use the New keyword or the CreateObject function, we create a new instance of a class.

Why would you want to encapsulate that?

VBA classes are Private by default: they can only be used within the project they are defined in. Class modules can also be made “Public, not creatable“, and used in other VBA projects that would add this VBA project as a reference (like you would reference the Scripting library, but now you’re referencing another .xlsm or .xlam). In the referencing VBA project, you can see and use the classes in that other referenced project, but you can’t create instances of them. You need a way to expose functionality to the referencing VBA project, to return instances of a public class.

You could have a standard module that exposes a public function that creates and returns the public class instance – but standard modules don’t quite encapsulate their members, and it’s up to the client code to properly qualify function calls or not: MyFactoryModule.CreateMyClass is just as valid as CreateMyClass, because public members of standard modules pollute the global namespace. An object whose sole responsibility is to create objects of a given type, keeps the global namespace clean – and that’s the factory patern in a nutshell.

But the referencing-project scenario isn’t the only reason to want a factory: sometimes creating a new instance of a class involves some amount of tedious setup code that can easily become redundant if we often need to create instances of that class in our code.

Set thing = New Something

thing.SomeProperty = someValue

thing.AnotherProperty = anotherValue

thing.OneMoreProperty = oneMoreValue

Set thing.OtherThing = New OtherThing '<~ imagine OtherThing also needs setup code!

'...

With a factory, that code only needs to exist in one place – and then DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself) and SRP (Single Responsibility Principle) are being adhered to, which generally means cleaner code that’s easier to maintain than if it didn’t.

Singleton

In OOP design patterns, factories are often combined with the Singleton pattern, because there only ever needs to be one single instance of a factory class. Given that the class can’t be created by the client code with the New keyword, setting the VB_PredeclaredId attribute to True essentially makes that class’ default instance an effective Singleton, at least from the perspective of the VBA project that’s referencing the project that defines the factory class.

I cannot think of a way to implement the Singleton pattern in VBA: there’s always a way something somewhere might somehow be able to create another instance of the class, or for more than one instance to exist at once. If VBA classes could have constructors (let alone static and/or private ones) it would be a different story, but it doesn’t so you’d need to implement some clunky instance-managing code involving state that’s external to the class… and I’d much rather have none of that. It’s simply not worth breaking encapsulation just to try and work around that kind of language-level limitation.

That doesn’t mean we can’t have nice things though.

Default Instances

If you’ve ever exported a VBA class module and opened it in Notepad, you’ve probably already seen this:

VERSION 1.0 CLASS

BEGIN

MultiUse = -1 'True

END

Attribute VB_Name = "Class1"

Attribute VB_GlobalNameSpace = False

Attribute VB_Creatable = False

Attribute VB_PredeclaredId = False

Attribute VB_Exposed = False

You know how every UserForm comes with a “default instance” for free? That’s because user forms have this attribute set to True, and that instructs VBA to create a global-scope object named after the type, so you can do this:

Without explicitly creating an instance of MyForm, we use one that’s already there. That’s not very OOP though – in fact it’s pretty much anti-OOP, since by doing that you’re not creating any objects, and because the automagic default instance global object is always named after the class, it makes the code look like we’re calling the Show method of the class itself, rather than the Show method of an instance of that class… So what’s the use of this attribute in an OOP discussion?

Using default instances as a prima facie singleton in VBA has shown to be the key that unlocks the true OOP capabilities of the language: by crafting an API that keeps the default instance stateless, we gain full control over exactly how our objects are shaped and can be used in other code.

With this level of control, we can now have effectively immutable, read-only objects in VBA.

Immutability

To be clear: we cannot achieve actual immutability in VBA – that would require constructors and readonly backing fields for our get-only properties. An object that is immutable is initialized with a number of values, and retains these exact same values for the entire lifetime of the object. In languages where that is enforced by the compiler, it removes implicit assumptions about objects’ state, makes objects simpler, and by extension the code easier to reason about, since there’s no mutable state to track. The Functional Programming (FP) paradigm really likes immutability, but the benefits are useful in OOP code as well.

In fact, exposing Property Let accessors for a property that has no business being written to by external code, breaks encapsulation and shouldn’t be done: the problem is that something, somewhere needs to supply the original value, and that is where factories come into play.

Example: Cross-Project Scenario

Say you have a Car class, with Make, Model and Manufacturer properties. It wouldn’t make sense for any of these properties to be changed after they’re assigned, right?

'@Folder("Examples.ReadOnlyInReferencingProject")

'@Exposed

Option Explicit

Private Type TCar

Make As Long

Model As String

Manufacturer As String

End Type

Private this As TCar

Public Property Get Make() As Long

Make = this.Make

End Property

Friend Property Let Make(ByVal value As Long)

this.Make = value

End Property

Public Property Get Model() As String

Model = this.Model

End Property

Friend Property Let Model(ByVal value As String)

this.Model = value

End Property

Public Property Get Manufacturer() As String

Manufacturer = this.Manufacturer

End Property

Friend Property Let Manufacturer(ByVal value As String)

this.Manufacturer = value

End Property

The seldom-used Friend access modifier makes the Model property read-only, at least for code located outside the VBA project this Car class is defined in: the Property Let member is only accessible from within the same project. However, a CarFactory class defined in the same VBA project can access the Friend members:

'@Folder("Examples.ReadOnlyInReferencingProject")

'@PredeclaredId

'@Exposed

Option Explicit

Public Function Create(ByVal carMake As Long, ByVal carModel As String, ByVal carManufacturer As String) As Car

Dim result As Car

Set result = New Car

result.Make = carMake

result.Model = carModel

result.Manufacturer = carManufacturer

Set Create = result

End Function

Because this CarFactory class has a PredeclaredId attribute set to True, the referencing VBA code can do this:

'@Folder("VBAProject")

Option Explicit

Public Sub DoSomething()

Dim myCar As Car

Set myCar = CarFactory.Create(2016, "Civic", "Honda")

MsgBox "We have a " & myCar.Make & " " & myCar.Manufacturer & " " & myCar.Model & " here."

'these assignments are illegal here, code won't compile if they're uncommented:

'myCar.Make = 2014

'myCar.Model = "Fit"

End Sub

And then the myCar object can’t be turned into a 2014 Honda Fit – not even by accident. Now that’s great, but more often than not, it’s within the project that we’d like to enjoy compiler-validated immutability – the problem is that within the project that defines the Car class, the Friend access modifier might as well be Public, for within that project, anything anywhere is able to access the Property Let members and turn our 2016 Honda into a 2017 Nissan.

If classes and public properties were all we had in our toolbox, that’s as far as we could get. Fortunately, VBA has more tricks up its sleeves.

Interface

In VBA a class module’s Public members define the default interface of an instance of that class, and while any other class can theoretically implement any other class’ default interface, in practice we actually use dedicated class modules to define formal abstract interfaces (just method stubs, no implementations) – to make sure things are confusing for everyone, we also call these special class modules… interfaces. In .NET we would use the interface keyword instead of class; in VBA we just use class modules for both.

For example we could add another class module, call it ICar (or whatever – but it’s typical if not expected to have abstract interface class names prefixed with an I), and then let it define the Get accessors we want the world to see:

'@Folder("Examples.ReadOnlyEverywhere")

'@Interface

Option Explicit

Public Property Get Make() As Long

End Property

Public Property Get Model() As String

End Property

Public Property Get Manufacturer() As String

End Property

One Interface, One Implementation: Caution!

It’s very much frowned upon in object-oriented code, to define an explicit abstract interface only to have one single class implement it: it’s a design smell because it makes things more complicated than they need to be… provided that the language has constructors and the ability to encapsulate readonly fields… which VBA does not.

So we’re going to bend the rules a bit here, tweak the accepted wisdom a bit: what we’re about to do is indeed going to enable polymorphism, but we’re not going to cover that here. For now we’re going to leverage interfaces for their ability to shape an object the way we need it to be, but it needs to be mentioned that in well-written OOP code, sticking an I in front of a class’ name and calling it an abstract interface is… not it – but that would be the subject of a discussion about abstraction levels, and abstraction in general: we’re just focusing on the mechanics here.

Implementation

In VBA we use the Implements keyword in a class module’s declarations section to tell the compiler that the class can be used with a particular interface. When we do that, we must implement every member of the interface we specified: not implementing them all would be a compile-time error.

Document Modules: Don’t.

While VBA will compile an Implements statement in any class module and that ThisWorkbook and worksheet modules are such modules, these document modules are also a special kind of class that’s best left handled by the host application that owns them: they will not be happy with implementing user classes. Corrupted project and sudden crash unhappy, I mean: whatever you do, do not use Implements in a document module’s code-behind. There are ways to work around this, using wrapper classes for example, where another class (the wrapper) implements the interface and talks to the worksheet.

So we have an ICar abstract interface that says any object implementing that interface has read-only properties Make, Model, and Manufacturer. The implementation might look like this – note this is the ReadOnlyCar class in the example code, but it could very well be the Car class above; I’ve kept them distinct to make the example code easier to follow along this article.

'@Folder("Examples.ReadOnlyEverywhere")

'@PredeclaredId

'@Exposed

Option Explicit

Implements ICar

Private Type TCar

Make As Long

Model As String

Manufacturer As String

End Type

Private this As TCar

Public Property Get Make() As Long

Make = this.Make

End Property

Friend Property Let Make(ByVal value As Long)

this.Make = value

End Property

Public Property Get Model() As String

Model = this.Model

End Property

Friend Property Let Model(ByVal value As String)

this.Model = value

End Property

Public Property Get Manufacturer() As String

Manufacturer = this.Manufacturer

End Property

Friend Property Let Manufacturer(ByVal value As String)

this.Manufacturer = value

End Property

Private Property Get ICar_Make() As Long

ICar_Make = this.Make

End Property

Private Property Get ICar_Manufacturer() As String

ICar_Manufacturer = this.Manufacturer

End Property

Private Property Get ICar_Model() As String

ICar_Model = this.Model

End Property

If we changed the return type of CarFactory.Create to the abstract ICar instead of the concrete Car, and made it return a New ReadOnlyCar reference, any existing calling code wouldn’t flinch, because the interface serves as a separation between the concrete class and the code that’s using it: it reduces the coupling and that makes the code more flexible – that factory could setup and return any implementation of the ICar interface, and as long as we adhere to the Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP), we are guaranteed to find a manufacturer in the Manufacturer property, a year in the Make property, and a model name in the Model property, because that’s what the “contract” of the ICar interface entails.

Notice the implementation is always Private? You will never ever want to change that: these methods are not meant to be exposed on the class’ default interface. That’s what the Implements keyword accomplishes: it tells VBA to expect (require, actually) certain specific members in that class. When an instance of the class is accessed through its ICar interface, what the code is seeing is the public ICar.Model, not the private ReadOnlyCar.ICar_Model.

Underscores: Don’t.

Notice the members implementing the interface always have that Interface_Member naming scheme? That underscore matters, possibly due to a bug in the VBA compiler, but if you try to make an interface with some Public Sub Do_Something() method, …VBA will refuse to recognize Private Sub IThing_Do_Something() as an implementation of that method. You should be avoiding underscores in VBA identifier names in general, anyway.

Factory Method

Depending on where we are in an OOP project, coupling with a concrete type can be perfectly fine. For example in the composition root at the entry point of a program, where objects and their dependencies are being created, we have no choice but to know about the concrete types – that doesn’t mean the rest of the code needs to know about them too though.

What we’re going to do here, is put everything we’ve seen above into practice, by simply moving the Create method from the factory class into the ReadOnlyCar class itself, and make the function return the ICar interface:

Public Function Create(ByVal carMake As Long, ByVal carModel As String, ByVal carManufacturer As String) As ICar

Dim result As ReadOnlyCar

Set result = New ReadOnlyCar

result.Make = carMake

result.Model = carModel

result.Manufacturer = carManufacturer

Set Create = result

End Function

Because the class has a VB_PredeclaredId attribute set to True, we get a free, global-scope default instance… that we’re going to keep stateless: it’s meaningless to assign that particular instance any values for its Make, Model, or Manufacturer properties. But that stateless default instance can be used as a factory by a referencing project if we make the class public, or by any other code that needs to create an instance of a ReadOnlyCar:

Dim myCar As ICar

Set myCar = ReadOnlyCar.Create(2014, "Honda", "Fit")

'myCar can only access the ICar members here.

Nothing can prevent us from creating a New ReadOnlyCar, but the Create factory method is more compelling to use, and now code that needs to initialize a series of ICar objects looks much cleaner than without.

What to use When

As we’ve seen, a factory method is useful when coupling isn’t a concern, and for all intents & purposes can be considered VBA’s take on parameterized object construction. A factory class is useful when the setup of an object is complex enough to warrant being pulled out of the class as its own responsibility, for it also shouldn’t be used when coupling matters. An abstract factory however, should be used when decoupling is needed (that would be when the class using the factory needs to be unit-tested but the factory then needs to supply an alternative implementation for testing purposes), and is a powerful tool in the injection of dependencies that cannot be initialized at the composition root. Big scary words? Read up on Dependency Injection in VBA!

Your project may not (probably doesn’t) need such complete decoupling, and that’s perfectly fine: OOP with tightly-coupled dependencies is still OOP – yes, even without any unit tests, and adhering to all SOLID principles is an art more than a science – but merely knowing that these techniques exist and what they are used for, will change how you reason about code: it’s no longer all about what the code does, it’s now also about how the components interact with each other, what responsibilities each object has; as the abstraction level increases, when to split things up becomes more and more obvious, and it all begins with interfaces and a better understanding of the nature of classes – once encapsulation is mastered, we can move on to explore abstraction; once abstraction is mastered, polymorphism will come much more easily. Factories being creational patterns (there are others), they make a perfect introduction to every single one of these concepts.

ThingFactoryFactory

Sometimes creating an object involves several components – in this simplified example we are creating cars with a few values, but what if creating an ICar object required us to provide some Engine object, which itself had its own dependencies? This is a contrived (and possibly bad) example, so bear with me, but let’s say every new ICar object needed to be injected with the same Engine instance… okay, definitely a bad example – the idea is that if every object ever created by a factory class needs a reference to some other object or value, then it becomes redundant to supply that reference or value through the factory’s ICar_Create method parameters.

Let’s say a car factory can only ever create new cars (hmm, what a crazy idea!) – taking in a carMake parameter for the year of manufacturing makes no sense then. And if a factory is making Nissan cars, they’re probably not making Ford or Toyota cars, so the carManufacturer parameter is really a property of the factory. Let’s make a simpler ISimplerCarFactory abstract factory interface that only takes the parameter we actually need: the carModel.

'@Folder("Examples.ReadOnlyEverywhere.AbstractFactory")

'@Interface

Option Explicit

Public Function Create(ByVal carModel As String) As ICar

End Function

Now we can see the actual benefits start to emerge – code using such a factory will be able to create an ICar without needing to specify a carManufacturer or a carMake; the factory implementation is now responsible for providing them:

'@Folder("Examples.ReadOnlyEverywhere.AbstractFactory")

'@PredeclaredId

Option Explicit

Implements ISimplerCarFactory

Private Type TFactory

Manufacturer As String

End Type

Private this As TFactory

Public Function Create(ByVal carManufacturer As String) As ICarFactory

Dim result As ManufacturerCarFactory

Set result = New ManufacturerCarFactory

result.Manufacturer = carManufacturer

Set Create = result

End Function

Public Property Get Manufacturer() As String

Manufacturer = this.Manufacturer

End Property

Public Property Let Manufacturer(ByVal value As String)

this.Manufacturer = value

End Property

Private Function ISimplerCarFactory_Create(ByVal carModel As String) As ICar

Dim result As ReadOnlyCar

result.Manufacturer = this.Manufacturer

result.Make = DateTime.Year

result.Model = carModel

Set ISimplerCarFactory_Create = result

End Function

As you can see, we’re now looking at a ManufacturerCarFactory class that can take its own dependencies, and thus has its own Create factory method that encapsulates them in private instance state. The advantages of such abstraction should become apparent now:

'@Folder("Examples")

Option Explicit

Public Sub DoSomething()

' let's make a factory that creates brand new cars whose Manufacturer is "Honda"

Dim factory As ISimplerCarFactory

Set factory = ManufacturerCarFactory.Create("Honda")

' let's make a bunch of cars

Dim cars As Collection

Set cars = CreateSomeHondaCars(factory)

' ...and now consume them

ListAllCars cars

End Sub

Private Function CreateSomeHondaCars(ByVal factory As ISimplerCarFactory) As Collection

'NOTE: this function doesn't know or care what specific ISimplerCarFactory it's working with.

Dim cars As Collection

Set cars = New Collection

cars.Add factory.Create("Civic")

cars.Add factory.Create("Accord")

cars.Add factory.Create("CRV")

Set CreateSomeCars = cars

End Function

Private Sub ListAllCars(ByVal cars As Collection)

'NOTE: this procedure doesn't know or care whas specific ICar implementation it's working with.

Dim c As ICar

For Each c In cars

Debug.Print c.Make, c.Manufacturer, c.Model

Next

End Sub

Running this code produces this output:

2020 Honda Civic

2020 Honda Accord

2020 Honda CRV

The Make and Manufacturer properties of every ICar issued by this abstract factory, are provided by the factory, such that none of this code needs to worry about these values. If we wanted CreateSomeCars to make Ford models instead, we would be giving it an ISimplerCarFactory implementation that would have been created with ManufacturerCarFactory.Create("Ford").

Back on Earth

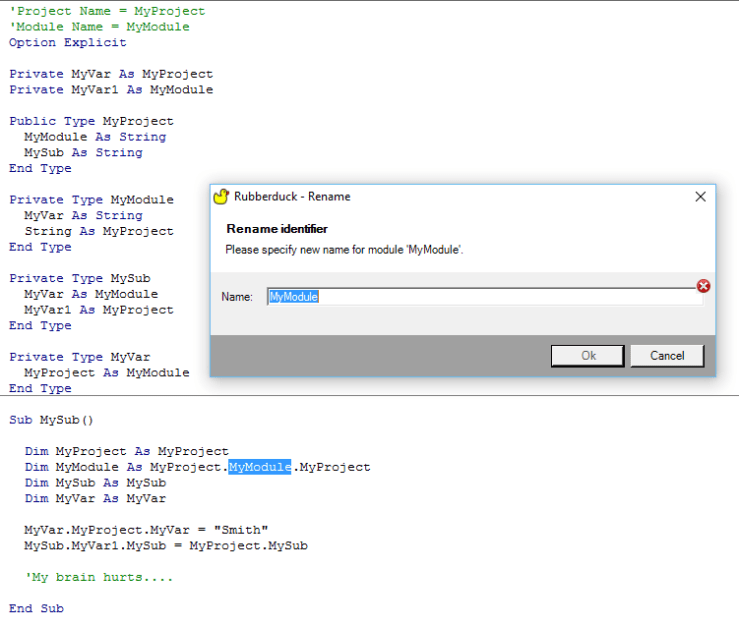

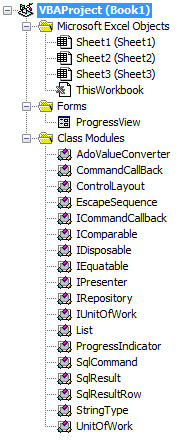

Discussions around OOP design patterns often turn to highly-abstracted components described in vague terms (“model-view-controller”, “repository”, “unit-of-work”, “command”, etc.) that, coming from procedural programming, feel convoluted and perhaps hard to follow. The sheer amount of class modules involved feels like nonsense, how does anyone even work with that many modules in a VBA project!

While Rubberduck’s Code Explorer and many other navigational enhancements completely address the code organization concerns, the fact remains that not all VBA code needs that much abstraction. The goal isn’t to learn how to write a macro here – the goal is to learn how VBA (and yes, VB6) code can scale to software-level projects. Small, perfectly-working and decently maintainable applications might have been written with a procedural paradigm, but OOP wouldn’t have been invented if scaling that up didn’t come with a number of design problems that demanded solutions – OOP design patterns propose upping the abstraction level and generalizing various common programming problems: that’s why they feel so far removed from cold-headed immediate applicability if you’re coming from small procedural projects and are just curious about classes and object-oriented code… it all feels overwhelmingly complicated stuff, with vague theoretical advantages that some praise and some others dispute, and sometimes rather energetically so.

Truth is, you don’t learn OOP by writing an ERP System, not anymore than you learn to swim by crossing the Atlantic. No project is too small to put these principles into application – sure the smaller the project the more silly & overkill having that much abstraction looks, but if you never cut your teeth on something small and keep OOP principles for the day you would actually need them, you may not have all the tools in your toolbox when you need them. Plus, it’s much easier to organically grow a code base that’s designed to scale in the first place, and then OOP principles being language-agnostic, what you’re learning here isn’t VBA, it’s Object-Oriented Programming, and that will stay with you well after you’ve moved on to, say, TypeScript.