Whenever any VBA code touches a worksheet, Excel clears its undo stack and if you want to undo what a macro just did, you’re out of luck. Of course nothing will magically restore the native stack, but what if we could actually undo/redo everything a macro did in a workbook, step by step – how could we even begin to make it work?

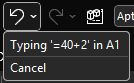

If we look at Excel’s own undo drop-down, we can get a glimpse of how to go about this:

Each individual action is represented by an object that describes this action, and presumably encapsulates information about the initial state of its target. So if A1 says 123 and we type ABC and hit undo, A1 still says 123 and if we hit redo, it says ABC again. Clearly there’s a type of “last in, first out” thing going on here: that’s why it’s called a stack – because you pile things on top and only ever take whichever is the first one on top.

We can implement similar stack behavior with a regular VBA.Collection, by adding items normally but only ever reading/removing (“popping”) the item at the last index.

But that’s just the basic mechanics. How do we abstract anything we could do to a worksheet? Well, we probably don’t need to cover everything, or we can have more or less atomic commands depending on our needs – but the idea is that we need something that’s undoable.

The entire source code related to this article can be found in the Examples repository.

Abstractions

If we can identify what we need out of an undoable command, then we can formalize it in an IUndoable interface: we know we need a Description, and surely Undo and Redo methods would be appropriate.

'@Interface

Option Explicit

'@Description("Undoes a previously performed action")

Public Sub Undo()

End Sub

'@Description("Redoes a previously undone action")

Public Sub Redo()

End Sub

'@Description("Describes the undoable action")

Public Property Get Description() As String

End Property

Commands and Context

We’ve talked about commands before – we’re going to take a page from the command pattern and have an ICommand interface like this:

'@Interface

Option Explicit

'@Description("Returns True if the command can be executed given the provided context")

Public Function CanExecute(ByVal Context As Object) As Boolean

End Function

'@Description("Executes an action given a context")

Public Sub Execute(ByVal Context As Object)

End Sub

This is pretty much the exact same abstraction we’ve seen before; how an undoable command differs is by how often it gets instantiated. If we don’t need a command to remember whether it ran and/or what context in was executed with, then we can create a single instance and reuse that instance whenever we need to run that command. But commands that implement IUndoable do know all these things, which means each instance can actually do the same thing but in a different context, and so we will need to create a new instance every time we run it.

The Context parameter is declared using the generic object type, because it’s the most specific we can get at that abstraction level without painting ourselves into a corner. Implementations will have to cast the parameter to a more specific type as needed. The role of this parameter is to encapsulate everything the command needs to do its thing, so let’s say we were writing a WriteRangeFormulaCommand; the context would need to give it a target Range and a formula String.

Similar to a ViewModel, the context class for a particular command is mostly specific to that command, and each context class can conceivably have little in common with any other such class. But we can still make them implement a common validation behavior, and so we can have an ICommandContext interface like this:

'@Interface

Option Explicit

'@Description("True if the model is valid in its current state")

Public Function IsValid() As Boolean

End Function

In the case of WriteRangeFormulaContext, the implementation could then look like this:

'@ModuleDescription("Encapsulates the model for a WriteToRangeFormulaCommand")

Option Explicit

Implements ICommandContext

Private Type TContext

Target As Excel.Range

Formula As String

End Type

Private This As TContext

'@Description("The target Range")

Public Property Get Target() As Excel.Range

Set Target = This.Target

End Property

Public Property Set Target(ByVal RHS As Excel.Range)

Set This.Target = RHS

End Property

'@Description("The formula or value to be written to the target")

Public Property Get Formula() As String

Formula = This.Formula

End Property

Public Property Let Formula(ByVal RHS As String)

This.Formula = RHS

End Property

Private Function ICommandContext_IsValid() As Boolean

If Not This.Target Is Nothing Then

If This.Target.Areas.Count = 1 Then

ICommandContext_IsValid = True

End If

End If

End Function

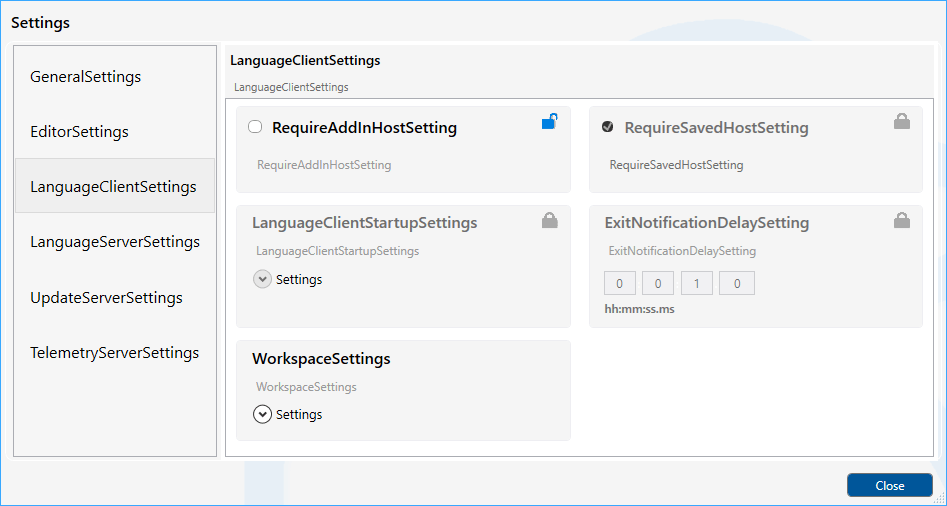

Rubberduck’s Encapsulate Field refactoring is once again being used to automatically expand the members of This into all these public properties, so granted it’s quite a bit of boilerplate code, but you don’t really need to actually write much of it: list what you need in the private type, declare an instance-level private field of that type, parse/refresh, and right-click the private field and select Rubberduck/Refactor/Encapsulate Field – and there’s likely nothing left to configure so just ok the dialog and poof the entire model class writes itself.

Implementation

So we add a WriteRangeFormulaCommand class and make it implement both ICommand and IUndoable. Why not have the undoable members in the command interface? Because interfaces should be clear and segregated, and only have members that are necessarily present in every implementation. If we wanted to implement a command that can’t be undone, we could, by simply omitting to implement IUndoable.

The encapsulated state of an undoable command is pretty straightforward: we have a reference to the context, something to hold the initial state, and then DidRun and DidUndo flags that the command can use to know what state it’s in and what can be done with it:

- If it wasn’t executed, DidRun is false

- If it was executed but not undone, DidUndo is false

- If it was undone, DidRun is necessarily true, and so is DidUndo

- If DidRun is true, we cannot execute the command again

- If DidUndo is true, we cannot undo again

- If DidRun is false, we cannot undo either

- Redo sets DidRun to false and then re-executes the command

Here’s the full implementation

'@ModuleDescription("An undoable command that writes to the Formula2 property of a provided Range target")

Option Explicit

Implements ICommand

Implements IUndoable

Private Type TState

InitialFormulas As Variant

Context As WriteToRangeFormulaContext

DidRun As Boolean

DidUndo As Boolean

End Type

Private This As TState

Private Function ICommand_CanExecute(ByVal Context As Object) As Boolean

ICommand_CanExecute = CanExecuteInternal(Context)

End Function

Private Sub ICommand_Execute(ByVal Context As Object)

ExecuteInternal Context

End Sub

Private Property Get IUndoable_Description() As String

IUndoable_Description = GetDescriptionInternal

End Property

Private Sub IUndoable_Redo()

RedoInternal

End Sub

Private Sub IUndoable_Undo()

UndoInternal

End Sub

Private Function GetDescriptionInternal() As String

Dim FormulaText As String

If Len(This.Context.Formula) > 20 Then

FormulaText = "formula"

Else

FormulaText = "'" & This.Context.Formula & "'"

End If

GetDescriptionInternal = "Write " & FormulaText & " to " & This.Context.Target.AddressLocal(RowAbsolute:=False, ColumnAbsolute:=False)

End Function

Private Function CanExecuteInternal(ByVal Context As Object) As Boolean

On Error GoTo OnInvalidContext

GuardInvalidContext Context

CanExecuteInternal = Not This.DidRun

Exit Function

OnInvalidContext:

CanExecuteInternal = False

End Function

Private Sub ExecuteInternal(ByVal Context As WriteToRangeFormulaContext)

GuardInvalidContext Context

SetUndoState Context

Debug.Print "> Executing action: " & GetDescriptionInternal

Context.Target.Formula2 = Context.Formula

This.DidRun = True

End Sub

Private Sub GuardInvalidContext(ByVal Context As Object)

If Not TypeOf Context Is ICommandContext Then Err.Raise 5, TypeName(Me), "An invalid context type was provided."

Dim SafeContext As ICommandContext

Set SafeContext = Context

If Not SafeContext.IsValid And Not TypeOf Context Is WriteToRangeFormulaContext Then Err.Raise 5, TypeName(Me), "An invalid context was provided."

End Sub

Private Sub SetUndoState(ByVal Context As WriteToRangeFormulaContext)

Set This.Context = Context

This.InitialFormulas = Context.Target.Formula2

End Sub

Private Sub UndoInternal()

If Not This.DidRun Then Err.Raise 5, TypeName(Me), "Cannot undo what has not been done."

If This.DidUndo Then Err.Raise 5, TypeName(Me), "Operation was already undone."

Debug.Print "> Undoing action: " & GetDescriptionInternal

This.Context.Target.Formula2 = This.InitialFormulas

This.DidUndo = True

End Sub

Private Sub RedoInternal()

If Not This.DidUndo Then Err.Raise 5, TypeName(Me), "Cannot redo what was never undone."

ExecuteInternal This.Context

This.DidUndo = False

End Sub

Quite a lot of this code would be identical in any other undoable command: only ExecuteInternal and UndoInternal methods would have to be different, and even then, only the part that actually performs or reverts the undoable action. Oh, and the GetDescriptionInternal string would obviously describe another command differently – here we say “Write (formula) to (target address)”, but another command might say “Set number format for (target address)” or “Format (edge) border of (target address)”. These descriptions can then be used in UI components to depict the undo/redo stack contents.

Management

There needs to be an object that is responsible for managing the undo and redo stacks, exposing simple methods to Push and Pop items, a way to Clear everything, and perhaps a method to get an array with all the command descriptions if you want to display them somewhere. The popping logic should push the retrieved item into the redo stack, and redoing an action should push it back into the undo stack.

Undo/Redo Mechanics

Enter UndoManager, which we’ll importantly be invoking from a predeclared instance to ensure we don’t have multiple undo/redo stacks around – any non-default instance usage would raise an error:

'@PredeclaredId

Option Explicit

Private UndoStack As Collection

Private RedoStack As Collection

Public Sub Clear()

Do While UndoStack.Count > 0

UndoStack.Remove 1

Loop

Do While RedoStack.Count > 0

RedoStack.Remove 1

Loop

End Sub

Public Sub Push(ByVal Action As IUndoable)

ThrowOnInvalidInstance

UndoStack.Add Action

End Sub

Public Function PopUndoStack() As IUndoable

ThrowOnInvalidInstance

Dim Item As IUndoable

Set Item = UndoStack.Item(UndoStack.Count)

UndoStack.Remove UndoStack.Count

RedoStack.Add Item

Set PopUndoStack = Item

End Function

Public Function PopRedoStack() As IUndoable

ThrowOnInvalidInstance

Dim Item As IUndoable

Set Item = RedoStack.Item(RedoStack.Count)

RedoStack.Remove RedoStack.Count

UndoStack.Add Item

Set PopRedoStack = Item

End Function

Public Property Get CanUndo() As Boolean

CanUndo = UndoStack.Count > 0

End Property

Public Property Get CanRedo() As Boolean

CanRedo = RedoStack.Count > 0

End Property

Public Property Get UndoState() As Variant

If Not CanUndo Then Exit Sub

ReDim Items(1 To UndoStack.Count) As String

Dim StackIndex As Long

For StackIndex = 1 To UndoStack.Count

Dim Item As IUndoable

Set Item = UndoStack.Item(StackIndex)

Items(StackIndex) = StackIndex & vbTab & Item.Description

Next

UndoState = Items

End Property

Public Property Get RedoState() As Variant

If Not CanRedo Then Exit Property

ReDim Items(1 To RedoStack.Count) As String

Dim StackIndex As Long

For StackIndex = 1 To RedoStack.Count

Dim Item As IUndoable

Set Item = RedoStack.Item(StackIndex)

Items(StackIndex) = StackIndex & vbTab & Item.Description

Next

RedoState = Items

End Property

Private Sub ThrowOnInvalidInstance()

If Not Me Is UndoManager Then Err.Raise 5, TypeName(Me), "Instance is invalid"

End Sub

Private Sub Class_Initialize()

Set UndoStack = New Collection

Set RedoStack = New Collection

End Sub

Private Sub Class_Terminate()

Set UndoStack = Nothing

Set RedoStack = Nothing

End Sub

A Friendly API

At this point we could go ahead and consume this API already, but things would quickly get very repetitive, so let’s make a CommandManager predeclared object that we can use to simplify how VBA code can work with undoable commands. I’m not going to bother with dependency injection here, and simply accept the tight coupling with the UndoManager class, which we’re simply going to wrap here:

'@PredeclaredId

Option Explicit

Public Sub WriteToFormula(ByVal Target As Range, ByVal Formula As String)

Dim Command As ICommand

Set Command = New WriteToRangeFormulaCommand

Dim Context As WriteToRangeFormulaContext

Set Context = New WriteToRangeFormulaContext

Set Context.Target = Target

Context.Formula = Formula

RunCommand Command, Context

End Sub

Public Sub SetNumberFormat(ByVal Target As Range, ByVal FormatString As String)

Dim Command As ICommand

Set Command = New SetNumberFormatCommand

Dim Context As SetNumberFormatContext

Set Context = New SetNumberFormatContext

Set Context.Target = Target

Context.FormatString = FormatString

RunCommand Command, Context

End Sub

'TODO expose new commands here

Public Sub UndoAction()

If UndoManager.CanUndo Then UndoManager.PopUndoStack.Undo

End Sub

Public Sub UndoAll()

Do While UndoManager.CanUndo

UndoManager.PopUndoStack.Undo

Loop

End Sub

Public Sub RedoAction()

If UndoManager.CanRedo Then UndoManager.PopRedoStack.Redo

End Sub

Public Sub RedoAll()

Do While UndoManager.CanRedo

UndoManager.PopRedoStack.Redo

Loop

End Sub

Public Property Get CanUndo() As Boolean

CanUndo = UndoManager.CanUndo

End Property

Public Property Get CanRedo() As Boolean

CanRedo = UndoManager.CanRedo

End Property

Private Sub RunCommand(ByVal Command As ICommand, ByVal Context As ICommandContext)

If Command.CanExecute(Context) Then

Command.Execute Context

StackUndoable Command

Else

Debug.Print "Command cannot be executed in this context."

End If

End Sub

Private Sub ThrowOnInvalidInstance()

If Not Me Is CommandManager Then Err.Raise 5, TypeName(Me), "Instance is invalid"

End Sub

Private Sub StackUndoable(ByVal Command As Object)

If TypeOf Command Is IUndoable Then

Dim Undoable As IUndoable

Set Undoable = Command

UndoManager.Push Undoable

End If

End Sub

Now that we have a way to transparently create and run and stack commands, all the complexity is hidden away behind simple methods; the calling code doesn’t even need to know there are commands and context classes involved, and it doesn’t even need to know about the UndoManager either.

Beyond

We could extend this with some FormatRangeFontCommand that could work with a context that encapsulates information about what we’re formatting as a single undoable operation, and how we’re formatting it. For example we could have properties like FontName, FontSize, FontBold, and so on, and as long as the command tracks the initial state of everything we’re going to be able to undo it all.

I actually extended it with a FormatRangeBorderCommand, but removed it because it isn’t really an undoable operation (I could probably have left it in without Implements IUndoable)… because unformatting borders in Excel is apparently much harder than formatting them: you format the bottom border of a target range, and then undo it by setting the bottom border line style and width to the original values… and the border remains there as if xlLineStyleNone had no effect whatsoever. Offsetting or extending the target to compensate (pretty sure it would work if the target was extended to the row underneath and it’s the interior-horizontal border that we then removed) would be playing with fire, so I just let it go instead of complexifying the example with edge-case handling.

It doesn’t shoot down the idea, but it does make a good reminder of the caveat that this isn’t a native undo operation: we’re actually just doing more things, except these new things bring the sheet back to the state it was before – at least that’s the intent.

An entirely undoable macro could look something like this:

Public Sub DoSomething()

With CommandManager

.WriteToFormula Sheet1.Range("A1"), "Hello"

.WriteToFormula Sheet1.Range("B1"), "World!"

.WriteToFormula Sheet1.Range("C1:C10"), "=RANDBETWEEN(0, 255)"

.WriteToFormula Sheet1.Range("D1:D10"), "=SUM($C$1:$C1)"

.SetNumberFormat Sheet1.Range("D1:D10"), "$#,##0.00"

End With

End Sub

Thoughts?