Note: this article was updated 2021-04-13 with screenshots from the latest v2.5.1.x pre-release build; the extract interface enhancements shown will green-release with v2.5.2.

We’ve seen how to leverage the default instance of a class module to define a stateless interface that’s perfect for a factory method. At the right abstraction level, most objects will not require more than just a few parameters. Often, parameters are related and can be abstracted/regrouped into their own object. Sometimes that makes things expressive enough. Other times, there’s just nothing we can do to work around the fact that we need to initialize a class with a dozen or more values.

The example code for this article can be found in our Examples repository.

A class with many properties

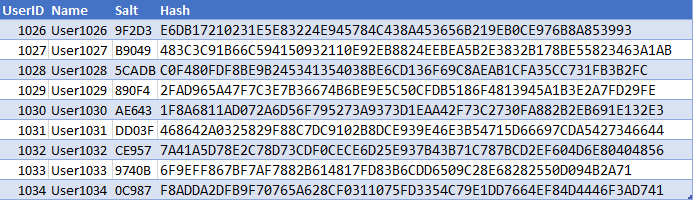

Such classes are actually pretty common; any entity object representing a database record would fit the bill. Let’s make a User class. We’re using Rubberduck, so this will be quick!

We start with a public field for each property we want:

Option Explicit

Public Id As String

Public UserName As String

Public FirstName As String

Public LastName As String

Public Email As String

Public EmailVerified As Boolean

Public TwoFactorEnabled As Boolean

Public PhoneNumber As String

Public PhoneNumberVerified As Boolean

Public AvatarUrl As String

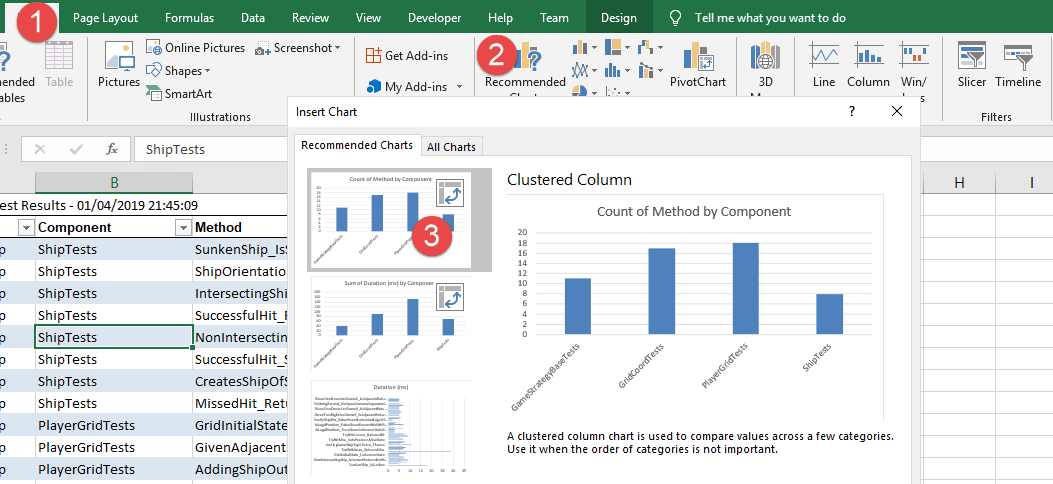

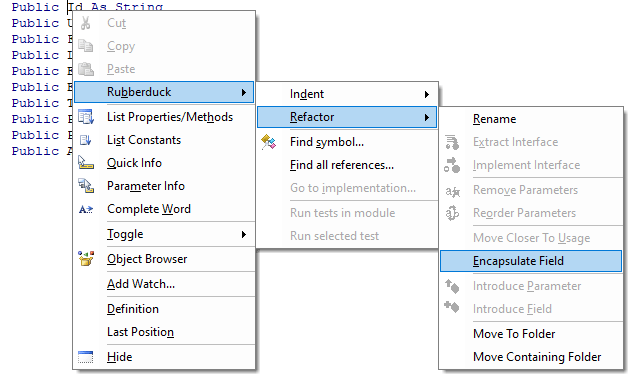

Now we hit Ctrl+` to trigger a parse, right-click any of the variables and select Encapsulate Field from the Refactor menu (or Ctrl+Shift+F if you haven’t tweaked the default hotkeys):

Check the wrap fields in private type box, then click the Select all button and hit OK.

Now the module looks like this, and all you had to do was to declare a bunch of public fields:

Option Explicit

Private Type TUser

Id As String

UserName As String

FirstName As String

LastName As String

Email As String

EmailVerified As Boolean

TwoFactorEnabled As Boolean

PhoneNumber As String

PhoneNumberVerified As Boolean

AvatarUrl As String

End Type

Private this As TUser

Public Property Get Id() As String

Id = this.Id

End Property

Public Property Let Id(ByVal value As String)

this.Id = value

End Property

Public Property Get UserName() As String

UserName = this.UserName

End Property

Public Property Let UserName(ByVal value As String)

this.UserName = value

End Property

Public Property Get FirstName() As String

FirstName = this.FirstName

End Property

Public Property Let FirstName(ByVal value As String)

this.FirstName = value

End Property

Public Property Get LastName() As String

LastName = this.LastName

End Property

Public Property Let LastName(ByVal value As String)

this.LastName = value

End Property

Public Property Get Email() As String

Email = this.Email

End Property

Public Property Let Email(ByVal value As String)

this.Email = value

End Property

Public Property Get EmailVerified() As Boolean

EmailVerified = this.EmailVerified

End Property

Public Property Let EmailVerified(ByVal value As Boolean)

this.EmailVerified = value

End Property

Public Property Get TwoFactorEnabled() As Boolean

TwoFactorEnabled = this.TwoFactorEnabled

End Property

Public Property Let TwoFactorEnabled(ByVal value As Boolean)

this.TwoFactorEnabled = value

End Property

Public Property Get PhoneNumber() As String

PhoneNumber = this.PhoneNumber

End Property

Public Property Let PhoneNumber(ByVal value As String)

this.PhoneNumber = value

End Property

Public Property Get PhoneNumberVerified() As Boolean

PhoneNumberVerified = this.PhoneNumberVerified

End Property

Public Property Let PhoneNumberVerified(ByVal value As Boolean)

this.PhoneNumberVerified = value

End Property

Public Property Get AvatarUrl() As String

AvatarUrl = this.AvatarUrl

End Property

Public Property Let AvatarUrl(ByVal value As String)

this.AvatarUrl = value

End Property

I love this feature! Rubberduck has already re-parsed the module, so next we right-click anywhere in the module and select the Extract Interface refactoring, and check the box to select all Property Get accessors (skipping Property Let):

Having a read-only interface for client code that doesn’t need the Property Let accessors makes an objectively cleaner API: assignments are recognized as invalid at compile time.

We get a read-only IUser interface for our efforts (!), and now the User class has an Implements IUser instruction at the top, …and these new members at the bottom:

Private Property Get IUser_ThingId() As String

IUser_ThingId = ThingId

End Property

Private Property Get IUser_UserName() As String

IUser_UserName = UserName

End Property

Private Property Get IUser_FirstName() As String

IUser_FirstName = FirstName

End Property

Private Property Get IUser_LastName() As String

IUser_LastName = LastName

End Property

Private Property Get IUser_Email() As String

IUser_Email = Email

End Property

Private Property Get IUser_EmailVerified() As Boolean

IUser_EmailVerified = EmailVerified

End Property

Private Property Get IUser_TwoFactorEnabled() As Boolean

IUser_TwoFactorEnabled = TwoFactorEnabled

End Property

Private Property Get IUser_PhoneNumber() As String

IUser_PhoneNumber = PhoneNumber

End Property

Private Property Get IUser_PhoneNumberVerified() As Boolean

IUser_PhoneNumberVerified = PhoneNumberVerified

End Property

Private Property Get IUser_AvatarUrl() As String

IUser_AvatarUrl = AvatarUrl

End Property

The scary part is that it feels as though if Extract Interface accounted for the presence of a Update: automagic implementation completed!Private Type in a similar way Encapsulate Field does, then even the TODO placeholder bits could be fully automated. Might be something to explore there…

Now we have our read-only interface worked out, if we go by previous posts’ teachings, , that is where we make our User class have a predeclared instance, and expose a factory method that I’d typically name Create:

'@Description "Creates and returns a new user instance with the specified property values."

Public Function Create(ByVal Id As String, ByVal UserName As String, ...) As IUser

'...

End Function

Without Rubberduck, in order to have a predeclared instance of your class you would have to export+remove the class module, locate the exported .cls file, open it in Notepad++, edit the VB_PredeclaredId attribute value to True, save+close the file, then re-import it back into your VBA project.

With Rubberduck, there’s an annotation for that: simply add '@PredeclaredId at the top of the class module, parse, and there will be a result for the AttributeValueOutOfSync inspection informing you that the class’ VB_PredeclaredId attribute value disagrees with the @PredeclaredId annotation, and then you apply the quick-fix you want, and you just might have synchronized hidden attributes across the with a single click.

'@PredeclaredId

Option Explicit

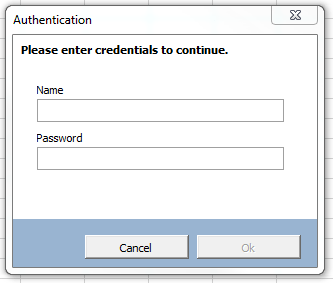

When it’s a factory method for a service class that takes in dependencies, 2-3 parameters is great, 5+ is suspicious. But here we’re taking in values, pure data – not some IFileWriter or other abstraction. And we need quite a lot of them (here 10, but who knows how many that can be!), and that’s a problem, because this is very ugly:

Set identity = User.Create("01234", "Rubberduck", "contact@rubberduckvba.com", False, ...)

Using named parameters can help:

Set identity = User.Create( _

Id:="01234", _

UserName:="Rubberduck", _

Email:="contact@rubberduckvba.com", _

EmailVerified:=False, _

Phone:="555-555-5555", _

PhoneVerified:=False, _

...)

But the resulting code still feels pretty loaded, and that’s with consistent line breaks. Problem is, that limits the number of factory method parameters to 20-ish (if we’re nice and stick to one per line), since that’s how many line continuations the compiler will handle for a single logical line of code.

Surely there’s a better way.

Building the Builder

I wrote about this pattern in OOP Design Patterns: The Builder, but in retrospect that article was really just a quick overview. Let’s explore the builder pattern.

I like to design objects from the point of view of the code that will be consuming them. In this case what we want to end up with, is something like this:

Set identity = UserBuilder.Create("01234", "Rubberduck") _

.WithEmail("contact@rubberduckvba.com", Verified:=False) _

.WithPhone("555-555-5555", Verified:=False) _

.Build

This solves a few problems that the factory method doesn’t:

- Optional arguments become explicitly optional member calls; long argument lists are basically eliminated.

- Say

IdandUserNameare required, i.e. aUserobject would be invalid without these values; the builder’s ownCreatefactory method can take these required values as arguments, and that way anyUserinstance that was built with aUserBuilderis guaranteed to at least have these values. - If we can provide a value for

EmailVerifiedbut not forEmail, or forPhoneVerifiedbut not forPhone, and neither are required… then with individual properties the best we can do is raise some validation error after the fact. With aUserBuilder, we can haveWithEmailandWithPhonemethods that take aVerifiedBoolean parameter along with the email/phone, and guarantee that ifEmailVerifiedis supplied, thenEmailis supplied as well.

I like to start from abstractions, so let’s add a new class module – but don’t rename it just yet, otherwise Rubberduck will parse it right away. Instead, copy the IUser interface into the new Class1 module, select all, and Ctrl+H to replace “Property Get ” (with the trailing space) with “Function With” (without the trailing space). Still with the whole module selected, we replace “String” and “Boolean” with “IUserBuilder”. The result should look like this:

'@Interface

Option Explicit

Public Function WithId() As IUserBuilder

End Function

Public Function WithUserName() As IUserBuilder

End Function

Public Function WithFirstName() As IUserBuilder

End Function

Public Function WithLastName() As IUserBuilder

End Function

Public Function WithEmail() As IUserBuilder

End Function

Public Function WithEmailVerified() As IUserBuilder

End Function

Public Function WithTwoFactorEnabled() As IUserBuilder

End Function

Public Function WithPhoneNumber() As IUserBuilder

End Function

Public Function WithPhoneNumberVerified() As IUserBuilder

End Function

Public Function WithAvatarUrl() As IUserBuilder

End Function

We’re missing a Build method that returns the IUser we’re building:

Public Function Build() As IUser

End Function

Now we add the parameters and remove the members we don’t want, merge the related ones into single functions – this is where we define the shape of our builder API: if we want to make it hard to create a User with a LastName but without a FirstName, or one with TwoFactorEnabled and PhoneNumberVerified set to True but without a PhoneNumber value… then with a well-crafted builder interface we can make it do exactly that.

Once we’re done, we can rename the class module to IUserBuilder, and that should trigger a parse. The interface might look like this now:

'@Interface

'@ModuleDescription("Incrementally builds a User instance.")

Option Explicit

'@Description("Returns the current object.")

Public Function Build() As IUser

End Function

'@Description("Builds a user with a first and last name.")

Public Function WithName(ByVal FirstName As String, ByVal LastName As String) As IUserBuilder

End Function

'@Description("Builds a user with an email address.")

Public Function WithEmail(ByVal Email As String, Optional ByVal Verified As Boolean = False) As IUserBuilder

End Function

'@Description("Builds a user with SMS-based 2FA enabled.")

Public Function WithTwoFactorAuthentication(ByVal PhoneNumber As String, Optional ByVal Verified As Boolean = False) As IUserBuilder

End Function

'@Description("Builds a user with an avatar at the specified URL.")

Public Function WithAvatar(ByVal Url As String) As IUserBuilder

End Function

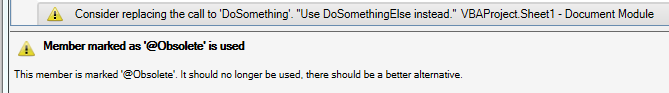

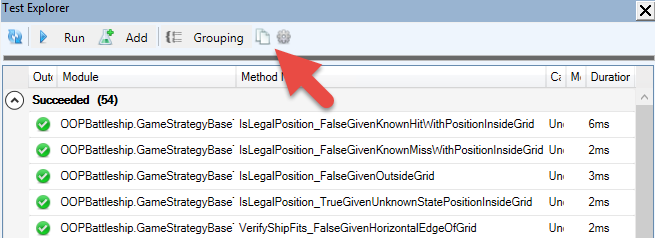

Then we can add another class module, and type Implements IUserBuilder under Option Explicit, then hit Ctrl+` to parse. Unless you disabled the “check if code compiles before parsing” setting (it’s enabled by default), you should be seeing this warning:

Click Yes to parse anyway (normally we only want compilable code, but in this case we know what we’re doing, I promise), then right-click somewhere in the Implements IUserBuilder statement, and select the Implement Interface refactoring:

The result is as follows, and makes a good starting point:

Option Explicit

Implements IUserBuilder

Private Function IUserBuilder_Build() As IUser

Err.Raise 5 'TODO implement interface member

End Function

Private Function IUserBuilder_WithName(ByVal FirstName As String, ByVal LastName As String) As IUserBuilder

Err.Raise 5 'TODO implement interface member

End Function

Private Function IUserBuilder_WithEmail(ByVal Email As String, Optional ByVal Verified As Boolean = False) As IUserBuilder

Err.Raise 5 'TODO implement interface member

End Function

Private Function IUserBuilder_WithTwoFactorAuthentication(ByVal PhoneNumber As String, Optional ByVal Verified As Boolean = False) As IUserBuilder

Err.Raise 5 'TODO implement interface member

End Function

Private Function IUserBuilder_WithAvatar(ByVal Url As String) As IUserBuilder

Err.Raise 5 'TODO implement interface member

End Function

We’re “building” an IUser object. So we have a module-level User object (we need the class’ default interface here, so that we can access the Property Let members), and each With method sets one property or more and then returns the current object (Me). That last part is critical, it’s what makes the builder methods chainable. We’ll need a Build method to return an encapsulated IUser object. So the next step will be to add a @PredeclaredId annotation and implement a Create factory method that takes the required values and injects the IUser object into the IUserBuilder instance we’re returning; then we can remove the members for these required values, leaving only builder methods for the optional ones. We will also add a value parameter of the correct type to each builder method, and make them all return the current object (Me). Once the class module looks like this, we can rename it to UserBuilder, and Rubberduck parses the code changes – note the @PredeclaredId annotation (needs to be synchronized to set the hidden VB_PredeclaredId attribute to True:

'@PredeclaredId

'@ModuleDescription("Builds a User object.")

Option Explicit

Implements IUserBuilder

Private internal As User

'@Description("Creates a new UserBuilder instance.")

Public Function Create(ByVal Id As String, ByVal UserName As String) As IUserBuilder

Dim result As UserBuilder

Set result = New UserBuilder

'@Ignore UserMeaningfulName FIXME

Dim obj As User

Set obj = New User

obj.Id = Id

obj.UserName = UserName

Set result.User = internal

Set Create = result

End Function

'@Ignore WriteOnlyProperty

'@Description("For property injection of the internal IUser object; only the Create method should be invoking this member.")

Friend Property Set User(ByVal value As IUser)

If Me Is UserBuilder Then Err.Raise 5, TypeName(Me), "Member call is illegal from default instance."

If value Is Nothing Then Err.Raise 5, TypeName(Me), "'value' argument cannot be a null reference."

Set internal = value

End Property

Private Function IUserBuilder_Build() As IUser

If internal Is Nothing Then Err.Raise 91, TypeName(Me), "Builder initialization error: use UserBuilder.Create to create a UserBuilder."

Set IUserBuilder_Build = internal

End Function

Private Function IUserBuilder_WithName(ByVal FirstName As String, ByVal LastName As String) As IUserBuilder

internal.FirstName = FirstName

internal.LastName = LastName

Set IUserBuilder_WithName = Me

End Function

Private Function IUserBuilder_WithEmail(ByVal Email As String, Optional ByVal Verified As Boolean = False) As IUserBuilder

internal.Email = Email

internal.EmailVerified = Verified

Set IUserBuilder_WithEmail = Me

End Function

Private Function IUserBuilder_WithTwoFactorAuthentication(ByVal PhoneNumber As String, Optional ByVal Verified As Boolean = False) As IUserBuilder

internal.TwoFactorEnabled = True

internal.PhoneNumber = PhoneNumber

internal.PhoneNumberVerified = Verified

Set IUserBuilder_WithTwoFactorAuthentication = Me

End Function

Private Function IUserBuilder_WithAvatar(ByVal Url As String) As IUserBuilder

internal.AvatarUrl = Url

Set IUserBuilder_WithAvatar = Me

End Function

Now, when I said default instances and factory methods (here too) are some kind of fundamental building block, I mean we’re going to be building on top of that, starting with this builder pattern; the Create method is intended to be invoked off the class’ default instance, like this:

Set builder = UserBuilder.Create(internalId, uniqueName)

The advantages are numerous, starting with the possibility to initialize the builder with everything it needs (all the required values), so that the client code can call Build and consume a valid User object right away.

Side note about this FIXME comment – there’s more to it than it being a signpost for the reader/maintainer:

'@Ignore UserMeaningfulName FIXME

Dim obj As User

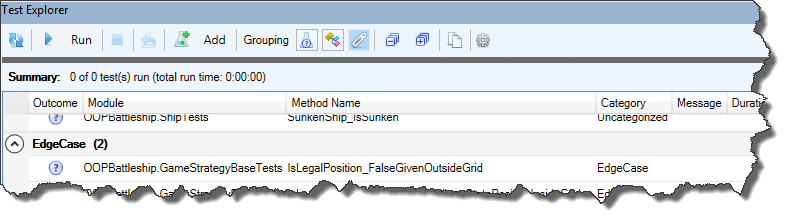

By default only TODO, BUG, and NOTE markers are picked up, but you can easily configure Rubberduck to find any marker you like in comments, and then the ToDo Explorer lets you easily navigate them all:

Another noteworthy observation:

'@Ignore WriteOnlyProperty

'@Description("For property injection of the internal IUser object; only the Create method should be invoking this member.")

Friend Property Set User(ByVal value As IUser)

If Me Is UserBuilder Then Err.Raise 5, TypeName(Me), "Member call is illegal from default instance."

If value Is Nothing Then Err.Raise 5, TypeName(Me), "'value' argument cannot be a null reference."

Set internal = value

End Property

Me is always the current object, as in, an instance of this class module, presenting the default interface of this class module: the If Me Is UserBuilder condition evaluates whether Me is the object known as UserBuilder – and right now there’s no such thing and the code doesn’t compile.

Synchronizing Attributes & Annotations

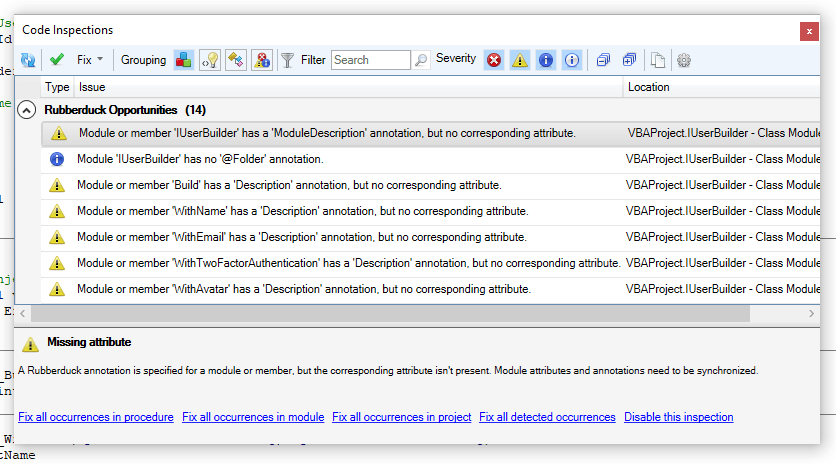

Rubberduck knows we mean that class to have a VB_PredeclaredId attribute value of True because of the @PredeclaredId annotation, but it’s still just a comment at this point. Bring up the inspection results toolwindow, and find the results for the MissingAttribute inspection under Rubberduck Opportunities:

That didn’t fix the VB_PredeclaredId attributes! Why?! The reason is that the attribute isn’t missing, only its value is out of sync. We’ll have to change this (pull requests welcome!), but for now you’ll find the AttributeValueOutOfSync inspection results under the Code Quality Issues group. If you group results by inspection, its miscategorization doesn’t matter though:

Adjust the attribute value accordingly (right-click the inspection result, or select “adjust attribute value(s)” from the “Fix” dropdown menu), and now your UserBuilder is ready to use:

Dim identity As IUser

Set identity = UserBuilder.Create(uniqueId, uniqueName) _

.WithName(first, last) _

.WithEmail(emailAddress) _

.Build

…and misuse:

Set UserBuilder.User = New User '<~ runtime error, illegal from default instance

Debug.Print UserBuilder.User.AvatarUrl '<~ compile error, invalid use of property

Set builder = New UserBuilder

Set identity = builder.Build '<~ runtime error 91, builder state was not initialized

Set builder = New UserBuilder

Set builder = builder.WithEmail(emailAddress) '<~ runtime error 91

Conclusions

Model classes with many properties are annoying to write, and annoying to initialize. Sometimes properties are required, other times properties are optional, others are only valid if another property has such or such value. This article has shown how effortlessly such classes can be created with Rubberduck, and how temporal coupling and other state issues can be solved using the builder creational pattern.

Using this pattern as a building block in the same toolbox as factory methods and other creational patterns previously discussed, we can now craft lovely fluent APIs that can chain optional member calls to build complex objects with many properties without needing to take a gazillion parameters anywhere.