Error-handling in VBA can easily get hairy. The best error handling code is no error handling code at all, and by writing our code at a high enough abstraction level, we can achieve exactly that – and leave the gory details in small, specialized, lower-abstraction procedures.

I’m growing rather fond of adapting the famous TryParse Pattern to VBA code, borrowed from the .NET landscape. Not really for performance reasons (VBA doesn’t deal with exceptions or stack traces), but for the net readability and abstraction gains. The crux of it is, you write a small, specialized function that returns a Boolean and takes a ByRef parameter for the return value – like this:

Public Function TryDoSomething(ByVal arg As String, ByRef outResult As Object) As Boolean

'only return True and set outResult to a valid reference if successful

End Function

Let the calling code decide what to do with a failure – don’t pop a MsgBox in such a function: it’s the caller’s responsibility to know what to do when you return False.

The pattern comes from methods like bool Int32.TryParse(string, out Int32) in .NET, where an exception-throwing Int32 Int32.Parse(string) equivalent method is also provided: whenever there’s a TryDoSomething method, there’s an equivalent DoSomething method that is more straightforward, but also more risky.

Applied consistently, the Try prefix tells us that the last argument is a ByRef parameter that means to hold the return value; the out prefix is Apps Hungarian (the actual original intent of “[Systems] Hungarian Notation”) that the calling code can see with IntelliSense, screaming “this argument is your result, and must be passed by reference” – even though IntelliSense isn’t showing the ByRef modifier:

This pattern is especially useful to simplify error handling and replace it with standard flow control, like If statements. For example you could have a TryFind function that takes a Range object along with something to find in that range, invokes Range.Find, and only returns True if the result isn’t Nothing:

Dim result As Range

If Not TryFind(Sheet1.Range("A:A"), "test", result) Then

MsgBox "Range.Find yielded no results.", vbInformation

Exit Sub

End If

result.Activate 'result is guaranteed to be usable here

It’s especially useful for things that can raise a run-time error you have no control over – like opening a workbook off a user-provided String input, opening an ADODB database connection, or anything else that might fail for any reason well out of your control, and all your code needs to know is whether it worked or not.

Public Function TryOpenConnection(ByVal connString As String, ByRef outConnection As ADODB.Connection) As Boolean

Dim result As ADODB.Connection

Set result = New ADODB.Connection

On Error GoTo CleanFail

result.Open connString

If result.State = adOpen Then

TryOpenConnection = True

Set outConnection = result

End If

CleanExit:

Exit Function

CleanFail:

Debug.Print "TryOpenConnection failed with error: " & Err.Description

Set result = Nothing

'Resume CleanExit

'Resume

End Function

The function returns True if the connection was successfully opened, False otherwise – regardless of whether that’s because the connection string is malformed, the server wasn’t found, or the connection timed out. If the calling code only needs to care about whether or not the connection succeeded, it’s perfect:

Dim adoConnection As ADODB.Connection

If Not TryOpenConnection(connString, adoConnection) Then

MsgBox "Could not connect to database.", vbExclamation

Exit Function

End If

'proceed to consume the successfully open connection

Note how Exit Sub/Exit Function are leveraged, to put a quick end to the doomed procedure’s misery… and let the rest of it confidently resume with the assurance that it’s working with an open connection, without a nesting level: having the rest of the procedure in an Else block would be redundant.

The .NET guideline about offering a pair of methods TryDoSomething/DoSomething are taken from Framework Design Guidelines, an excellent book with plenty of very sane conventions – but unless you’re writing a VBA Framework “library” project, it’s almost certainly unnecessary to include the error-throwing sister method. YAGNI: You Ain’t Gonna Need It.

Cool. Can it be abused though?

Of course, and easily so: any TryDoSomethingThatCouldNeverRaiseAnError method would be weird. Keep the Try prefix for methods that make you dodge that proverbial error-handling bullet. Parameters should generally passed ByVal, and if there’s a result to return, it should be returned as a Function procedure’s return value.

If a function needs to return more than one result and you find yourself using ByRef parameters for outputs, consider reevaluating its responsibilities: there’s a chance it might be doing more than it should. Or if the return values are so closely related they could be expressed as one thing, consider extracting them into a small class.

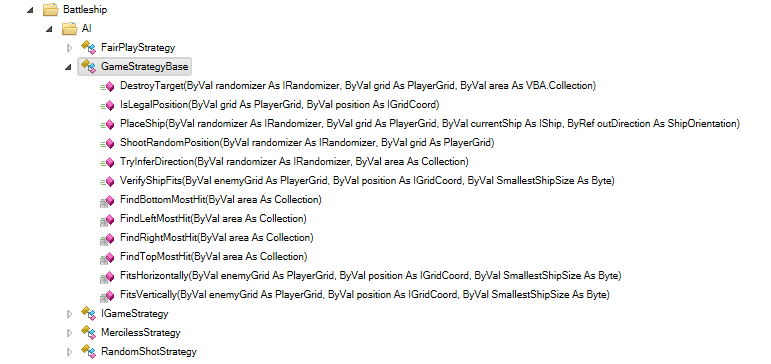

The GridCoord class in the OOP Battleship project is a great example of this: systematically passing X and Y values together everywhere quickly gets old, and turning them into an object suddenly gives us the ability to not only pass them as one single entity, but we also get to compare it with another coordinate object for equality or intersection, or to evaluate whether that other coordinate is adjacent; the object knows how to represent itself as a String value, and the rest of the code consumes it through the read-only IGridCoord interface – all that functionality would have to be written somewhere else, if X and Y were simply two Long integer values.