I wrote about this unfortunately hard-to-discover feature in 2017, but a lot has happened since then, and there’s 5 times more of you now! The wiki is essentially up-to-date, but I’m not sure of its viewership. So here’s a recap of annotations in the late Rubberduck 2.4.1.x pre-release builds, that 2.5.0.x will launch with.

What we call “annotations” are special comments that look like these:

'@Folder("MyProject.Abstract")

'@ModuleDescription("An interface that describes an object responsible for something.")

'@Interface

'@Exposed

'@Description("Does something")

Public Sub DoSomething()

End Sub

Syntax

Rubberduck’s parser includes a grammar rule that captures these special comments, such that we “see” them like any other language syntax element (tokens), and can analyze them as such, too.

The syntax is rather simple, and is made to look like a procedure call – note that string arguments must be surrounded with double quotes:

'@AnnotationName arg1, arg2, "string argument"

If desired, parentheses can be used, too:

'@AnnotationName(arg1, arg2)

'@AnnotationName("string argument")

Whether you use one notation or the other is entirely up to personal preference, both are completely equivalent. As with everything else, consistency should be what matters.

There’s an inspection that flags illegal/unsupported annotations that you, if you’re using this @PseudoSyntax for other purposes, will probably want to disable: that’s done by setting its severity level to DoNotShow in the inspection settings, or by simply clicking “disable this inspection” from the inspection results toolwindow.

Keep in mind that while they are syntactically comments as far as VBA is concerned, to Rubberduck parsing the argument list of an annotation needs to follow strict rules. This parses correctly:

'@Folder "Some.Sub.Folder" @ModuleDescription "Some description" : some comment

Without the : instruction separator token, the @ModuleDescription annotation parses as a regular comment. After : though, anything goes.

There are two distinct types of annotation comments: some annotations are only valid at module level, and others are only valid at member level.

Module Annotations

Module-level annotations apply to the entire module, and must appear in that module’s declarations section. Personally, I like having them at the very top, above Option Explicit. Note that if there’s no declaration under the last annotation, and no empty line, then the placement becomes visually ambiguous – even though Rubberduck correctly understands it, avoid this:

Option Explicit

'@Description("description here")

Public Sub DoSomething() '^^^ is this the module's or the procedure's annotation?

End Sub

Let it breathe – always have an empty line between the end of the module’s declarations section (there should always at least be Option Explicit there) and the module’s body:

Option Explicit

'@Folder("MyProject") : clearly belongs to the module

'@Description("description here")

Public Sub DoSomething() '^^^ clearly belongs to the procedure

End Sub

What follows is a list of every single module-level annotation currently supported (late v2.4.1.x pre-release builds), that v2.5.0 will launch with.

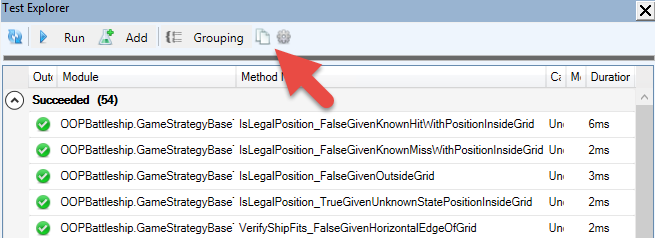

@Folder

The Visual Basic Editor regroups modules in its Project Explorer toolwindow, by component type: you get a folder for your “Modules”, another folder for your “Class Modules”; if you have userforms they’re all under a “Forms” folder, and then the document modules are all lumped under some “Microsoft Excel Objects” folder (in an Excel host, anyway). While this grouping is certainly fine for tiny little automation scripts, it makes navigation wildly annoying as soon as a project starts having multiple features and responsibilities.

In a modern IDE like Visual Studio, code files can be regrouped by functionality into a completely custom folder hierarchy: you get to have a form in the same folder as the presenter class that uses it, for example. With Rubberduck’s Code Explorer toolwindow, you get to do exactly the same, and the way you do this is with @Folder annotations.

'@Folder("Root.Parent.Child")

Option Explicit

The @Folder annotation takes a single string argument representing the “virtual folder” a module should appear under, where a dot (.) denotes a sub-folder – a bit like .NET namespaces. Somewhere deep in the history of this annotation, there’s a version that’s even named @Namespace. “Folder” was preferred though, because “Namespace” was deemed too misleading for VBA/VB6, given the language doesn’t support them: all module names under a given project must still be unique. The Code Explorer toolwindow uses these annotations to build the folder hierarchy to organize module nodes under, but the folders don’t actually exist: they’re just a representation of the annotation comments in existing modules – and that is why there is no way to create a new, empty folder to drag-and-drop modules into.

It is strongly recommended to adopt a standard and consistent PascalCase naming convention for folder names: future Rubberduck versions might very well support exporting modules accordingly with these folder annotations, so these “virtual folders” might not be “virtual” forever; by using a PascalCase naming convention, you not only adopt a style that can be seamlessly carried into the .NET world; you also make your folders future-proof. Avoid spaces and special characters that wouldn’t be legal in a folder name under Windows.

The ModuleWithoutFolder inspection (under “Rubberduck Opportunities”), if enabled, will warn you of modules where this annotation is absent. By default, Rubberduck’s Code Explorer will put all modules under a single root folder named after the VBA project. While this might seem rather underwhelming, it was a deliberate decision to specifically not re-create the “by component type” grouping of the VBE and encourage our users to instead regroup modules by functionality.

@IgnoreModule

The @IgnoreModule annotation is automatically added by the “Ignore in Module” inspection quick-fix, which effectively disables a specific code inspection, but only in a specific module. This can be useful for inspections that have false positives, such as procedure not used firing results in a module that contains public parameterless procedures that are invoked from ActiveX controls on a worksheet, which Rubberduck isn’t seeing (hence the false positives), but that are otherwise useful, such that you don’t necessarily want to completely disable the inspection (i.e. set its severity level to DoNotShow).

If no arguments are specified, this annotation will make all inspections skip the module. To skip a specific inspection, you may provide its name (minus the Inspection suffix) as an argument. To ignore multiple inspections, you can separate them with commas like you would any other argument list:

'@IgnoreModule ProcedureNotUsed, ParameterNotUsed

Alternatively, this annotation may be supplied multiple times:

'@IgnoreModule ProcedureNotUsed

'@IgnoreModule ParameterNotUsed

Use the : instruction separator to terminate the argument list and add an explanatory comment as needed:

'@IgnoreModule ProcedureNotUsed : These are public macros attached to shapes on Sheet1

Note that the arguments (inspection names) are not strings: enclosing the inspection names in string literals will not work.

@TestModule

This was the very first annotation supported by Rubberduck. This annotation is only legal in standard/procedural modules, and marks a module for test discovery: the unit testing engine will only scan these modules for unit tests. This annotation does not support any parameters.

@ModuleDescription(“value”)

Given a string value, this annotation can be used to control the value of the module’s hidden VB_Description attribute, which determines the module’s “docstring” – a short description that appears in the VBE’s Object Browser, and that Rubberduck displays in its toolbar and in the Code Explorer.

Because Rubberduck can’t alter module attributes in document modules, this annotation is illegal in modules representing objects owned by the host application (i.e. “document” modules), such as Worksheet modules and ThisWorkbook.

@PredeclaredId

This annotation does not support any parameters, and can be used to control the value of the hidden VB_PredeclaredId attribute, which determines whether a class has a default instance. When a class has a default instance, its members can be invoked without an instance variable (rather, using an implicit one named after the class itself), like you did every single time you’ve ever written UserForm1.Show – but now you get to have a default instance for your own classes, and this opens up a vast array of new possibilities, most notably the ability to now write factory methods in the same class module as the class being factory-created, effectively giving you the ability to initialize new object instances with parameters, just like you would if VBA classes had parameterized constructors:

Dim something As Class1

Set something = Class1.Create("test", 42)

@Exposed

VBA classes are private by default: this means if you make a VBA project that references another, then you can’t access that class from the referencing project. By setting the class’ instancing property to PublicNotCreatable, a referencing project is now able to consume the class (but the class can only be instantiated inside the project that defines it… and that’s where factory methods shine).

This annotation visibly documents that the class’ instancing property has a non-default value (this can easily be modified in the VBE’s properties toolwindow).

@Interface

In VBA every class modules defines a public interface: every class can Implements any other class, but not all classes are created equal, and in the vast majority of the time what you want to follow the Implements keyword will be the name of an abstract interface. An abstract interface might look like this:

'@Interface

Option Explicit

Public Sub DoSomething()

End Sub

Adding this annotation to a module serves as metadata that Rubberduck uses when analyzing the code: the Code Explorer will display these modules with a dedicated “interface” icon, and an inspection will be able to flag procedures with a concrete implementation in these modules.

@NoIndent

Rubberduck’s Smart Indenter port can indent your entire VBA project in a few milliseconds, but automatically indenting a module can have undesirable consequences, such as losing hidden member attributes. Use this annotation to avoid accidentally wiping hidden attributes in a module: the indenter will skip that module when bulk-indenting the project.

Member Annotations

Member-level annotations apply to the entire procedure they’re annotating, and must be located immediately over the procedure’s declaration:

'@Description("Does something")

Public Sub DoSomething()

'...

End Sub

As with module annotations, multiple member annotations can be specified for the same procedure – either by stacking them, or enumerating them one after the other:

'@DefaultMember

'@Description("Gets the item at the specified index")

Public Property Get Item(ByVal index As Long) As Object

'...

End Property

Member annotations that aren’t immediately above the procedure declaration, will be flagged as illegal by the IllegalAnnotation inspection:

'@Description("Does something") : <~ annotation is illegal/misplaced

Public Sub DoSomething()

'...

End Sub

@Description

This very useful annotation controls the value of the member’s hidden VB_Description attribute, which defines a docstring that appears in the bottom panel of the Object Browser when the member is selected – Rubberduck also displays this content in the context-sensitive (selection-dependent) label in the Rubberduck VBIDE toolbar.

@Ignore

Similar to @IgnoreModule, the purpose of the member-level @Ignore annotation is to get specific inspections to ignore the annotated procedure: it works identically.

@DefaultMember

Only one single member of a class can be the class’ default member. Default members should generally be avoided, but they are very useful for indexed Item properties of custom collection classes. This annotation takes no arguments.

@Enumerator

Custom collections that need to support For Each enumeration are required to have a member that returns an IUnknown, and hidden flags and attributes: this annotation clearly identifies the special member, and gets the hidden flags and attributes right every time.

'@Enumerator

Public Property Get NewEnum() As IUnknown

Set NewEnum = encapsulatedCollection.[_NewEnum]

End Property

@ExcelHotkey

This rather specific annotation works in Excel-hosted VBA projects (as of this writing its absence may cause inspection false positives in other host applications, like Microsoft Word).

When the VBA project is hosted in Microsoft Excel, you can use this annotation to assign hotkeys using the same mechanism Excel uses to map hotkeys to recorded macros.

'@ExcelHotkey "D" : Ctrl+Shift+D will invoke this procedure in Excel

Public Sub DoSomething()

'...

End Sub

'@ExcelHotkey "d" : Ctrl+D will invoke this procedure in Excel

Public Sub DoSomethingElse()

'...

End Sub

Note that the annotation will work regardless of whether the argument is treated as a string literal or not – only the first character of the annotation argument is used, and its case determines whether the Shift key is involved in the hotkey combination (all hotkeys involve the Ctrl key): use an uppercase letter for a Ctrl+Shift hotkey.

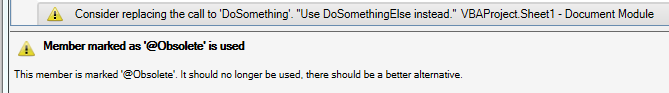

@Obsolete

Code under continued maintenance is constantly evolving, and sometimes in order to avoid breaking existing call sites, a procedure might need to be replaced by a newer version, while keeping the old one around: this annotation can be used to mark the old version as obsolete with an explanatory comment, and inspections can flag all uses of the obsolete procedure:

'@Obsolete("Use DoSomethingElse instead.")

Public Sub DoSomething()

'...

End Sub

Public Sub DoSomethingElse()

'...

End Sub

Test Method Annotations

These annotations have been in Rubberduck for a very long time, and they are actually pretty easy to discover since they are automatically added by Rubberduck when adding test modules and test methods using the UI commands – but since Test Settings can be configured to not include setup & teardown stubs, it can be easy to forget they exist and what they do.

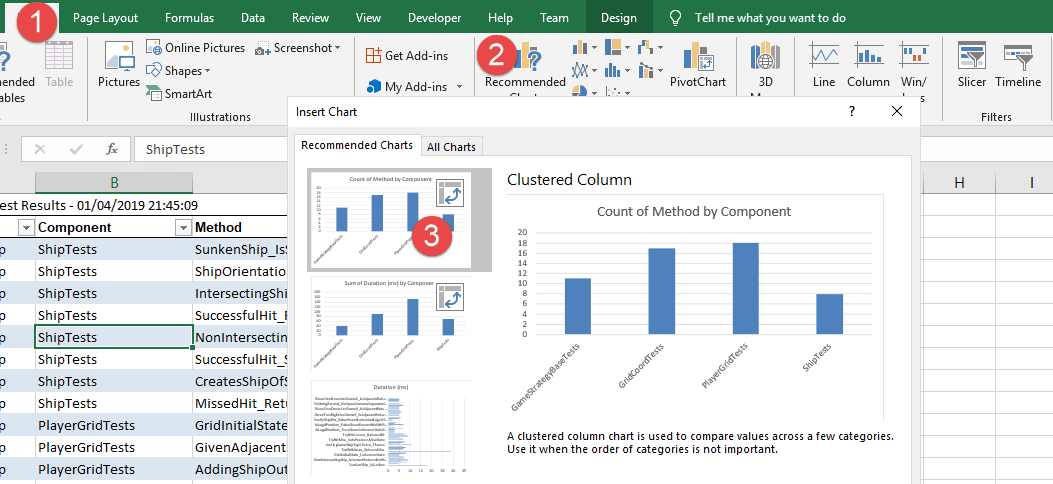

@TestMethod

This annotation is used in test modules to identify test methods: every test must be marked with this annotation in order to be discoverable as a test method. It is automatically added by Rubberduck’s “add test method” commands, but needs to be added manually if a test method is typed manually in the editor rather than inserted by Rubberduck.

This annotation supports a string argument that determines the test’s category, which appears in the Test Explorer toolwindow and enables grouping by category. If no category argument is specified, “Uncategorized” is used as a default:

@TestMethod("Some Category")

Private Sub TestMethod1()

'...

End Sub

The other @TestXxxxx member annotations are used for setup & teardown. If test settings have the “Test module initialization/cleanup” option selected, then @ModuleInitialize and @ModuleCleanup procedure stubs are automatically added to a new test module. If test settings have “Test method initialization/cleanup” selected, then @TestInitialize and @TestCleanup procedure stubs are automatically added a new test modules.

@TestInitialize

In test modules, this annotation marks procedures that are invoked before every single test in the module. Use that method to run setup/initialization code that needs to execute before each test. Each annotated procedure is invoked, but the order of invocation cannot be guaranteed… however there shouldn’t be a need to have more than one single such initialization method in the module.

@TestCleanup

Also used in test modules, this annotation marks methods that are invoked after every single test in that test module. Use these methods to run teardown/cleanup code that needs to run after each test. Again, each annotated procedure is invoked, but the order of invocation cannot be guaranteed – and there shouldn’t be a need to have more than one single such cleanup method in the module.

@ModuleInitialize

Similar to @TestInitialize, but for marking procedures that are invoked once for the test module, before the tests start running. Use these procedures to run setup code that needs to run before the module’s tests begin to run; each annotated procedure will be invoked, but the order of invocation cannot be guaranteed. Again, only one such initialization procedure should be needed, if any.

@ModuleCleanup

Similar to @TestCleanup, but for marking procedures that are invoked once for the test module, after all tests in the module have executed. Use these procedures to run teardown/cleanup code that needs to run after all module’s tests have completed; each annotated procedure will be invoked, but the order of invocation isn’t guaranteed. Only one such cleanup procedure should be needed, if any.

Annotations are one of Rubberduck’s most useful but unfortunately also one of its most obscure and hard-to-discover features. Fortunately, we have plans to surface them as right-click context menu commands in the 2.5.x release cycle.