Authenticating the user of our application is a common problem, with common pitfalls – some innocuous, some fatal. It’s also a solved problem, with a fairly standard solution. Unfortunately, it’s also a problem that’s too often solved with naive, “good-enough” solutions that make any security expert twitch.

The vast majority of scenarios don’t need any custom authentication. Accessing a SQL Server database? Use Windows Authentication! Windows Auth not possible? Use SQL Authentication over a secure network! App authentication isn’t for authenticating a user with a server. More like, the application itself needs a concept of users and privileges granted to certain groups of users, and so we need to prompt the user for a user name and a password. What could possibly go wrong?

Security First: Threat Model Assessment

The first question we need to ask ourselves, is literally “what could possibly go wrong?” — as in, what are we trying to do? If the answer is along the lines of:

- Enhance user experience with tailored functionality

- Grouping users into “roles” for easier management

- Prevent accidental misuse of features

…then you’re on the right track. However if you’re thinking more in terms of…

- Prevent intentional misuse of features

- Securely prevent groups of users from accessing functionalities

- Securely

$(anything)

…then you’re going to need another kind of approach. VBA code is not secure, period. Even if the VBA project is password-protected, the VBE can be tricked into unlocking it with some clever Win32 API calls. So, the threat model should take into account that a power user that wants to see your code… will likely succeed …pretty easily, too.

That doesn’t mean VBA code gets a pass to do everything wrong! If you’re going to do password authentication, you might as well do it right.

Where to store users’ passwords?

We’ve all done this:

Private Const ADMIN_PWD As String = "@Dm!n"

…without realizing that the code of a VBA project – even locked – is compressed into a binary file that’s zipped with the rest of the Excel host document. But nothing prevents anyone from peeking at it, say, with Notepad++

Obviously, hard-coding passwords is the worst possible idea: we need somewhere safe, right?

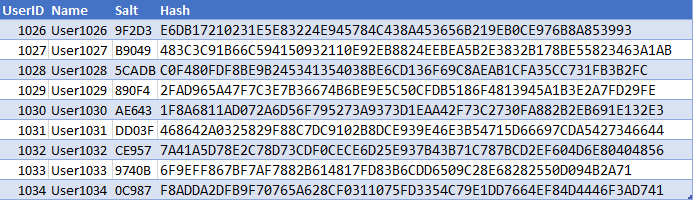

Truth is, not really. You could have everything you need in a hidden worksheet that anyone can see if they like; a database server is ideal, of course, but not necessary, if parts of your host document can be used as one (looking at you too, Microsoft Access).

The reason it doesn’t matter if the “passwords table” is compromised, is because you do not store passwords, period. Not even encrypted: the “passwords table” contains nothing that can be processed (decrypted) and then used as a password.

What you store is a hash of the users’ passwords, never the passwords themselves. For example, if a user’s password was password and we hashed it with the SHA256 hashing algorithm, we would be storing the following value:

5e884898da28047151d0e56f8dc6292773603d0d6aabbdd62a11ef721d1542d8

Contrary to encryption and encoding, there is by definition no way to revert a hash value back to the original string password. It’s possible that some random string that’s not password might produce the same hash value (i.e. a hash collision) – but very (very very) unlikely, at least with SHA256 or higher.

There are many different hashing algorithms, producing values of varying length, at varying speeds: with cryptographically secure requirements, using slow algorithms that produce values with a low risk of collision will be preferred (harder/longer to brute-force). Other applications might use a faster MD5 hash that’s “good enough” if not very secure, for many things but a password.

Now obviously, if any two users have the same password, their SHA256 hash would be the same. If that’s a concern (it should be), then the solution is to use a salt: prepend a random string to the password, and hash the salted password string – assuming all users use a different salt value (it can be safely stored alongside the user record), then it becomes impossible to tell whether any two users have the same password just by looking at the table contents… and this is why a hidden worksheet is a perfectly fine place to store your user passwords if you can’t use a database for whatever reason.

Storing a salted password hash prevents “translating” the hash values wholesale, using a lookup/”rainbow” table that contains common passwords and their corresponding hash representation. Even if one password is compromised, other users with the same password wouldn’t be, because their hash is different, thanks to the “salt” bytes.

Whether we code in C#, PHP, JavaScript, Python, Java, ..or VBA, there’s simply not a single valid reason to store user passwords in plain text. But how do we get that hash value out of a password string in the first place?

Hashing with VBA

There’s… no built-in support whatsoever for hashing in VBA… but nothing says we can’t make explicit late binding and the .NET Framework work for us! Note that we’re invoking the ComputeHash_2 method, because it’s an overload of the ComputeHash method that takes the byte array we want to give it. COM/VBA doesn’t support method overloading, so when .NET exposes overloads to COM, it appends _2 to the method name, _3, _4, and so on for each overload. The order depends on… the order they were written to the IDL, which means you could… just trust Stack Overflow on that one, and go with ComputeHash_2:

Public Function ComputeHash(ByVal value As String) As String

Dim bytes() As Byte

bytes = StrConv(value, vbFromUnicode)

Dim algo As Object

Set algo = CreateObject("System.Security.Cryptography.SHA256Managed")

Dim buffer() As Byte

buffer = algo.ComputeHash_2(bytes)

ComputeHash = ToHexString(buffer)

End Function

Private Function ToHexString(ByRef buffer() As Byte) As String

Dim result As String

Dim i As Long

For i = LBound(buffer) To UBound(buffer)

result = result & Hex(buffer(i))

Next

ToHexString = result

End Function

This code would feel right at home in a SHA256Managed standard module, or it could be a class that implements some IHashAlgorithm interface with a ComputeHash method – and with it we have everything we need to start handling password-based authentication in VBA …by today’s best practices.

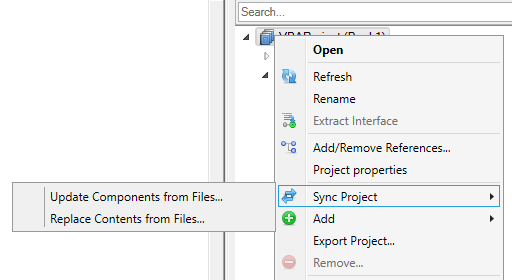

What follows is an object-oriented approach to leveraging this function in a VBA project that needs to authenticate a user. An online copy of this code can be downloaded from GitHub: https://github.com/rubberduck-vba/examples/tree/master/Authentication

IHashAlgorithm

I like having functionality neatly abstracted, so instead of just having a public ComputeHash function that computes the SHA256 hash for a given string, I’ll have a class module formalizing what a hash algorithm does:

'@Folder("Authentication.Hashing")

'@ModuleDescription("An interface representing a hashing algorithm.")

'@Interface

Option Explicit

'@Description("Computes a hash for the given string value.")

Public Function ComputeHash(ByVal value As String) As String

End Function

One implementation would be this SHA256Managed class module:

'@Folder("Authentication.Hashing")

'@PredeclaredId

Option Explicit

Implements IHashAlgorithm

Private base As HashAlgorithmBase

'@Description("Factory method creates and returns a new instance of this class.")

Public Function Create() As IHashAlgorithm

Set Create = New SHA256Managed

End Function

Private Sub Class_Initialize()

Set base = New HashAlgorithmBase

End Sub

Private Function IHashAlgorithm_ComputeHash(ByVal value As String) As String

Dim bytes() As Byte

bytes = StrConv(value, vbFromUnicode)

Dim algo As Object

Set algo = CreateObject("System.Security.Cryptography.SHA256Managed")

Dim buffer() As Byte

buffer = algo.ComputeHash_2(bytes)

IHashAlgorithm_ComputeHash = base.ToHexString(buffer)

End Function

By coding against an interface (i.e. by invoking ComputeHash off the IHashAlgorithm interface), we are making the code easier to modify later without breaking things: if a functionality needs a MD5 hash algorithm instead of SHA256, we can implement a MD5Managed class and inject that, and no client code needs to be modified, because the code doesn’t care what specific algorithm it’s working with, as long as it implements the IHashAlgorithm interface.

The HashAlgorithmBase class is intended to be used by all implementations of IHashAlgorithm, so we’re using composition to simulate inheritance here (the coupling is intended, there’s no need to inject that object as a dependency). The class simply exposes the ToHexString function, so that any hashing algorithm can get a hex string out of a byte array:

'@Folder("Authentication.Hashing")

'@ModuleDescription("Provides common functionality used by IHashAlgorithm implementations.")

Option Explicit

'@Description("Converts a byte array to a string representation.")

Public Function ToHexString(ByRef buffer() As Byte) As String

Dim result As String

Dim i As Long

For i = LBound(buffer) To UBound(buffer)

result = result & Hex(buffer(i))

Next

ToHexString = result

End Function

At this point we can already test the hashing algorithm in the immediate pane:

?SHA256Managed.Create().ComputeHash("abc")

BA7816BF8F1CFEA414140DE5DAE2223B0361A396177A9CB410FF61F2015ADThe next step is to create an object that’s able to take user credentials, and tell its caller whether or not the credentials are good. This is much simpler than it sounds like.

UserAuthModel

The first thing we need to address, is the data we’re going to be dealing with – the model. In the case of a dialog that’s prompting for a user name and a password, our model is going to be a simple class exposing Name and Password read/write properties, and here an IsValid property returns True if the Name and Password values aren’t empty:

'@Folder("Authentication")

Option Explicit

Private Type TAuthModel

Name As String

Password As String

IsValid As Boolean

End Type

Private this As TAuthModel

Public Property Get Name() As String

Name = this.Name

End Property

Public Property Let Name(ByVal value As String)

this.Name = value

Validate

End Property

Public Property Get Password() As String

Password = this.Password

End Property

Public Property Let Password(ByVal value As String)

this.Password = value

Validate

End Property

Public Property Get IsValid() As Boolean

IsValid = this.IsValid

End Property

Private Sub Validate()

this.IsValid = Len(this.Name) > 0 And Len(this.Password) > 0

End Sub

Since this isn’t a model for changing a password, the validation logic doesn’t need to worry about the password’s length and/or content – only that a non-empty value was provided; your mileage may vary!

If we wanted the UI to provide a ComboBox dropdown to pick a user name, then the model class would need to encapsulate an array or collection that contains the user names, and that array or collection would be provided by another component.

IAuthService

When my object-oriented brain thinks “authentication”, what shapes up in my mind is a simple interface that exposes a single Boolean-returning function that takes user credentials, and returns True when authentication succeeds with the provided credentials.

Something like this:

'@Folder("Authentication")

'@ModuleDescription("An interface representing an authentication mechanism.")

'@Interface

Option Explicit

'@Description("True if the supplied credentials are valid, False otherwise.")

Public Function Authenticate(ByVal model As UserAuthModel) As Boolean

End Function

If we have a hidden worksheet with a table containing the user names, salt values, and hashed passwords for all users, then we could implement this interface with some WorksheetAuthService class that might look like this:

'@Folder("Authentication")

'@ModuleDescription("A service responsible for authentication.")

'@PredeclaredId

Option Explicit

Implements IAuthService

Private Type TAuthService

Algorithm As IHashAlgorithm

End Type

Private Type TUserAuthInfo

Salt As String

Hash As String

End Type

Private this As TAuthService

Public Function Create(ByVal hashAlgorithm As IHashAlgorithm)

With New WorksheetAuthService

Set .Algorithm = hashAlgorithm

Set Create = .Self

End With

End Function

Public Property Get Self() As IHashAlgorithm

Set Self = Me

End Property

Public Property Get Algorithm() As IHashAlgorithm

Set Algorithm = this.Algorithm

End Property

Public Property Set Algorithm(ByVal value As IHashAlgorithm)

Set this.Algorithm = value

End Property

Private Function GetUserAuthInfo(ByVal user As String, ByRef outInfo As TUserAuthInfo) As Boolean

'gets the salt value & password hash for the specified user; returns false if user can't be retrieved.

On Error GoTo CleanFail

With PasswordsSheet.Table

Dim nameColumnIndex As Long

nameColumnIndex = .ListColumns("Name").Index

Dim saltColumnIndex As Long

saltColumnIndex = .ListColumns("Salt").Index

Dim hashColumnIndex As Long

hashColumnIndex = .ListColumns("PasswordHash").Index

Dim userRowIndex As Long

userRowIndex = Application.WorksheetFunction.Match(user, .ListColumns(nameColumnIndex).DataBodyRange, 0)

outInfo.Salt = Application.WorksheetFunction.Index(.ListColumns(saltColumnIndex).DataBodyRange, userRowIndex)

outInfo.Hash = Application.WorksheetFunction.Index(.ListColumns(hashColumnIndex).DataBodyRange, userRowIndex)

End With

GetUserAuthInfo = True

CleanExit:

Exit Function

CleanFail:

Debug.Print Err.Description

Debug.Print "Unable to retrieve authentication info for user '" & user & "'."

outInfo.Salt = vbNullString

outInfo.Hash = vbNullString

GetUserAuthInfo = False

Resume CleanExit

End Function

Private Function IAuthService_Authenticate(ByVal model As UserAuthModel) As Boolean

Dim info As TUserAuthInfo

If Not model.IsValid Or Not GetUserAuthInfo(model.Name, outInfo:=info) Then Exit Function

Dim pwdHash As String

pwdHash = this.Algorithm.ComputeHash(info.Salt & model.Password)

IAuthService_Authenticate = (pwdHash = info.Hash)

End Function

If we only look at the IAuthService_Authenticate implementation, we can easily tell what’s going on:

- If for any reason we can’t identify the specified user / get its authentication info, we bail

- Using the user’s

Saltstring, we use the hashing algorithm’sComputeHashmethod to get a hash string for the specified password. - Authentication succeeds if the hashed salted password matches the stored hash string for that user.

Note how the provided model.Password string isn’t being copied anywhere, or compared against anything.

The GetUserAuthInfo function is being considered an implementation detail here, but could easily be promoted to its own IUserAuthInfoProvider interface+implementation: the role of that function is to get the Salt and PasswordHash values for a given user, and here we’re pulling that from a table on a worksheet, but other implementations could be pulling it from a database: this is a concern in its own right, and could very easily be argued to belong in its own class, abstracted behind its own interface.

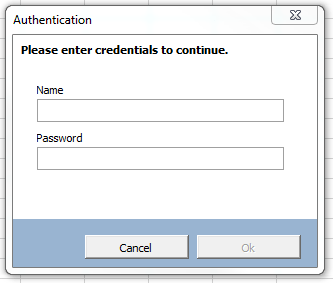

IAuthView

If we’re going to have a dialog for the user to enter their credentials into, then everything we’ve seen about the Model-View-Presenter UI design pattern is applicable here – we already have our model, and now we need an abstraction for a view.

'@Folder("Authentication")

'@Interface

Option Explicit

'@Description("Shows the view as a modal dialog. Returns True unless the dialog is cancelled.")

Public Function ShowDialog() As Boolean

End Function

Public Property Get UserAuthModel() As UserAuthModel

End Property

From an abstract standpoint, the view is nothing more than a function that displays the dialog and returns False if the dialog was cancelled, True otherwise.

The concrete implementation will be a UserForm that includes two textboxes, two command buttons, and a few labels – like this:

The code-behind for the form is very simple:

Changehandlers for the textboxes assign the corresponding model propertyClickhandlers for the command buttons simplyHidethe form- A

Createfactory method takes aUserAuthModelobject reference - Model is exposed for property injection (only the factory method uses this property)

'@Folder("Authentication")

'@PredeclaredId

Option Explicit

Implements IAuthView

Private Type TAuthDialog

UserAuthModel As UserAuthModel

IsCancelled As Boolean

End Type

Private this As TAuthDialog

Public Function Create(ByVal model As UserAuthModel) As IAuthView

If model Is Nothing Then Err.Raise 5, TypeName(Me), "Model cannot be a null reference"

Dim result As AuthDialogView

Set result = New AuthDialogView

Set result.UserAuthModel = model

Set Create = result

End Function

Public Property Get UserAuthModel() As UserAuthModel

Set UserAuthModel = this.UserAuthModel

End Property

Public Property Set UserAuthModel(ByVal value As UserAuthModel)

Set this.UserAuthModel = value

End Property

Private Sub OnCancel()

this.IsCancelled = True

Me.Hide

End Sub

Private Sub Validate()

OkButton.Enabled = this.UserAuthModel.IsValid

End Sub

Private Sub CancelButton_Click()

OnCancel

End Sub

Private Sub OkButton_Click()

Me.Hide

End Sub

Private Sub NameBox_Change()

this.UserAuthModel.Name = NameBox.Text

Validate

End Sub

Private Sub PasswordBox_Change()

this.UserAuthModel.Password = PasswordBox.Text

Validate

End Sub

Private Sub UserForm_QueryClose(Cancel As Integer, CloseMode As Integer)

If CloseMode = VbQueryClose.vbFormControlMenu Then

Cancel = True

OnCancel

End If

End Sub

Private Function IAuthView_ShowDialog() As Boolean

Me.Show vbModal

IAuthView_ShowDialog = Not this.IsCancelled

End Function

Private Property Get IAuthView_UserAuthModel() As UserAuthModel

Set IAuthView_UserAuthModel = this.UserAuthModel

End Property

The important thing to note, is that the form itself doesn’t do anything: it’s just an I/O device your code uses to interface with the user – nothing more, nothing less. It collects user-provided data into a model, and ensures the dialog validates that model.

The form knows about the UserAuthModel and its properties (Name, Password, IsValid), and nothing else. It doesn’t know how to get a list of user names to populate a dropdown so that the user can pick a name from a list (that could be done, but then the model would need a UserNames property). It doesn’t know how to verify whether the provided password string is correct. It’s …just not its job to do anything other than relay messages to & from the user.

IAuthPresenter

We have a UserAuthModel that holds the user-supplied credentials. We have a WorksheetAuthService that can take these credentials and tell us if they’re good, using any IHashAlgorithm implementation. We’re missing an object that pieces it all together, and that’s the job of a presenter.

What we want is for the code that needs an authenticated user, to be able to consume a simple interface, like this:

'@Folder("Authentication")

'@ModuleDescription("Represents an object that can authenticate the current user.")

'@Interface

Option Explicit

'@Description("True if user is authenticated")

Public Property Get IsAuthenticated() As Boolean

End Property

'@Description("Prompts for user credentials")

Public Sub Authenticate()

End Sub

Now, any class that encapsulates functionality that involves authenticating the current user can be injected with an IAuthPresenter interface, and when IsAuthenticated is True we know our user is who they say they are. And if we inject the same instance everywhere, then the user only needs to enter their credentials once for the authentication state to be propagated everywhere – without using any globals!

'@Folder("Authentication")

'@PredeclaredId

'@ModuleDescription("Represents an object responsible for authenticating the current user.")

Option Explicit

Implements IAuthPresenter

Private Type TPresenter

View As IAuthView

AuthService As IAuthService

IsAuthenticated As Boolean

End Type

Private this As TPresenter

Public Function Create(ByVal service As IAuthService, ByVal dialogView As IAuthView) As IAuthPresenter

Dim result As AuthPresenter

Set result = New AuthPresenter

Set result.AuthService = service

Set result.View = dialogView

Set Create = result

End Function

Public Property Get AuthService() As IAuthService

Set AuthService = this.AuthService

End Property

Public Property Set AuthService(ByVal value As IAuthService)

Set this.AuthService = value

End Property

Public Property Get View() As IAuthView

Set View = this.View

End Property

Public Property Set View(ByVal value As IAuthView)

Set this.View = value

End Property

Private Sub IAuthPresenter_Authenticate()

If Not this.View.ShowDialog Then Exit Sub

this.IsAuthenticated = this.AuthService.Authenticate(this.View.UserAuthModel)

End Sub

Private Property Get IAuthPresenter_IsAuthenticated() As Boolean

IAuthPresenter_IsAuthenticated = this.IsAuthenticated

End Property

At this point any standard module macro (aka entry point) can create the presenter and its dependencies:

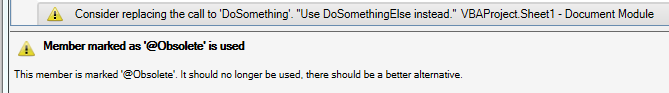

Public Sub DoSomething()

Dim model As UserAuthModel

Set model = New UserAuthModel

Dim dialog As IAuthView

Set dialog = AuthDialogView.Create(model)

Dim algo As IHashAlgorithm

Set algo = SHA256Managed.Create()

Dim service As IAuthService

Set service = WorksheetAuthService.Create(algo)

Dim presenter As IAuthPresenter

Set presenter = AuthPresenter.Create(service, dialog)

presenter.Authenticate

If presenter.IsAuthenticated Then

MsgBox "Welcome!", vbInformation

Else

MsgBox "Access denied", vbExclamation

End If

End Sub

If this were real application code, instead of consuming the presenter it would be injecting it into some class instance, and invoking a method on that class. This composition root (where we compose the application / instantiate and inject all the dependencies) would probably be in the Workbook_Open handler, so that the authentication state can be shared between components.

Authorisation

Up to this point, we only cared for authentication, i.e. identifying the current user. While very useful, it doesn’t tell us who’s authorized to do what. Without some pretty ugly code that special-cases specific users (e.g. “Admin”), we’re pretty limited here.

One proven solution, is to use role-based authorisations. Users belong to a “group” of users, and it’s the “group” of users that’s authorized to do things, not users themselves.

In order to do this, the WorksheetAuthService implementation needs to be modified to add a RoleId member to the TUserAuthInfo, and the IAuthService.Authenticate method could return a Long instead of a Boolean, where 0 would still mean a failed authentication, but any non-zero value would be the authenticated user’s RoleId.

Roles could be defined by an enum (note the default / 0 value):

Public Enum AuthRole

Unauthorized = 0

Admin

Maintenance

Auditing

End Enum

Or, role membership could be controlled in Active Directory (AD), using security groups – in that case you’ll want your IAuthService implementation to query AD instead of a worksheet, and the IAuthPresenter implementation to hold the current user’s role ID along with its authentication status.

There are many ways to go about implementing authentication, and many implementation-specific concerns. For example, if you’re querying a database for this, you’ll want to use commands and proper parameterization to avoid the problems associated with SQL Injection vulnerabilities: maybe a user named Robert');DROP TABLE USERS;-- isn’t part of your threat model, but can Tom O'Neil log onto your system without breaking anything?

Regardless of the approach, if you’re comparing the user’s plain-text password input with the plain-text password stored in $(storage_medium), you’re doing it wrong – whether that’s in VBA or not.