So you’ve written a beautiful piece of code, a macro that does everything it needs to do… the only thing is that, well, it takes a while to complete. Oh, it’s as efficient as it gets, you’ve put it up for peer review on Code Review Stack Exchange, and the reviewers helped you optimize it. You need a way to report progress to your users.

There are several possible solutions.

Updating Application.StatusBar

If the macro is written in such a way that the user could very well continue using Excel while the code is running, then why disturb their workflow – simply updating the application’s status bar is definitely the best way to do it.

You could use a small procedure to do it:

Public Sub UpdateStatus(Optional ByVal msg As String = vbNullString)

Dim isUpdating As Boolean

isUpdating = Application.ScreenUpdating

'we need ScreenUpdating toggled on to do this:

If Not isUpdating Then Application.ScreenUpdating = True

'if msg is empty, status goes to "Ready"

Application.StatusBar = msg

'make sure the update gets displayed (we might be in a tight loop)

DoEvents

'if ScreenUpdating was off, toggle it back off:

Application.ScreenUpdating = isUpdating

End Sub

It’s critical to understand that the user can change the ActiveSheet at any time, so if your long-running macro involves code that implicitly (or explicitly) refers to the active worksheet, you’ll run into problems. Rubberduck has an inspection that specifically locates these implicit references though, so you’ll do fine.

Modeless Progress Indicator

A commonly blogged-about solution is to display a modeless UserForm and update it from the worker code. I dislike this solution, for several reasons:

- The user is free to interact with the workbook and change the

ActiveSheet at any time, but the progress is reported in an invasive dialog that the user needs to drag around to move out of the way as they navigate the worksheets.

- It pollutes the worker code with form member calls; the worker code decides when to display and when to hide and destroy the form.

- It feels like a work-around: we’d like a modal UserForm, but we don’t know how to make that work nicely.

“Smart UI” Modal Progress Indicator

If we only care to make it work yesterday, a “Smart UI” works: we get a modal dialog, so the user can’t use the workbook while we’re modifying it. What’s the problem then?

The form is running the show – the “worker” code needs to be in the code-behind, or invoked from it. That is the problem: if you want to reuse that code, in another project, you need to carefully scrap the worker code. If you want to reuse that code in the same project, you’re out of luck – either you duplicate the “indicator” code and reimplement the other “worker” code in another form’s code-behind, or the form now has “modes” and some conditional logic determines which worker code will get to run: you can imagine how well that scales if you have a project that needs a progress indicator for 20 features.

“Smart UI” can’t be good either. So, what’s the real solution then?

A Reusable Progress Indicator

We want a modal indicator (so that the user can’t interfere with our modifications), but one that doesn’t run the show: we want the UserForm to be responsible for nothing more than keeping its indicator representative of the current progress.

This solution is based on a piece of code I posted on Code Review back in 2015; you can find the original post here. This version is better though, be it only because of how it deals with cancellation.

The solution is implemented across two components: a form, and a class module.

ProgressView

First, a UserForm, obviously.

Nothing really fancy here. The form is named ProgressView. There’s a ProgressLabel, a 228×24 DecorativeFrame, and inside that Frame control, a ProgressBar label using the Highlight color from the System palette. Here’s the complete code-behind:

Option Explicit

Private Const PROGRESSBAR_MAXWIDTH As Integer = 224

Public Event Activated()

Public Event Cancelled()

Private Sub UserForm_Activate()

ProgressBar.Width = 0

RaiseEvent Activated

End Sub

Public Sub Update(ByVal percentValue As Single, Optional ByVal labelValue As String, Optional ByVal captionValue As String)

If labelValue vbNullString Then ProgressLabel.Caption = labelValue

If captionValue vbNullString Then Me.Caption = captionValue

ProgressBar.Width = percentValue * PROGRESSBAR_MAXWIDTH

DoEvents

End Sub

Private Sub UserForm_QueryClose(Cancel As Integer, CloseMode As Integer)

If CloseMode = VbQueryClose.vbFormControlMenu Then

Cancel = True

RaiseEvent Cancelled

End If

End Sub

Clearly this isn’t a Smart UI: the form doesn’t even have a concept of “worker code”, it’s blissfully unaware of what it’s being used for. In fact, on its own, it’s pretty useless. Modally showing the default instance of this form leaves you with only the VBE’s “Stop” button to close it, because its QueryClose handler is actively preventing the user from “x-ing out” of it. Obviously that form is rather useless on its own – it’s not responsible for anything beyond updating itself and notifying the ProgressIndicator when it’s ready to start reporting progress – or when the user means to cancel the long-running operation.

ProgressIndicator

This is the class that the client code will be using. A PredeclaredId attribute gives it a default instance, which is used to expose a factory method.

Here’s the full code – walkthrough follows:

Option Explicit

Private Declare PtrSafe Sub Sleep Lib "kernel32" (ByVal dwMilliseconds As Long)

Private Const DEFAULT_CAPTION As String = "Progress"

Private Const DEFAULT_LABEL As String = "Please wait..."

Private Const ERR_NOT_INITIALIZED As String = "ProgressIndicator is not initialized."

Private Const ERR_PROC_NOT_FOUND As String = "Specified macro or object member was not found."

Private Const ERR_INVALID_OPERATION As String = "Worker procedure cannot be cancelled by assigning to this property."

Private Const VBERR_MEMBER_NOT_FOUND As Long = 438

Public Enum ProgressIndicatorError

Error_NotInitialized = vbObjectError + 1001

Error_ProcedureNotFound

Error_InvalidOperation

End Enum

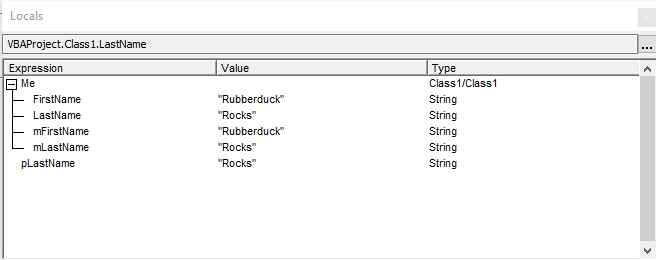

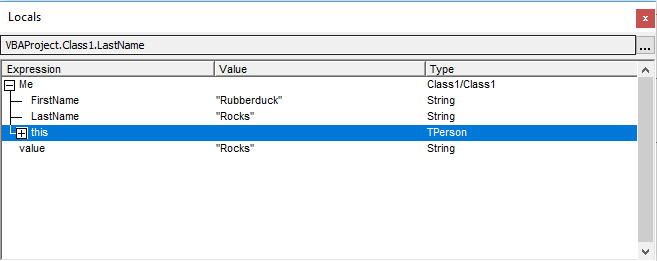

Private Type TProgressIndicator

procedure As String

instance As Object

sleepDelay As Long

canCancel As Boolean

cancelling As Boolean

currentProgressValue As Double

End Type

Private this As TProgressIndicator

Private WithEvents view As ProgressView

Private Sub Class_Initialize()

Set view = New ProgressView

view.Caption = DEFAULT_CAPTION

view.ProgressLabel = DEFAULT_LABEL

End Sub

Private Sub Class_Terminate()

Set view = Nothing

Set this.instance = Nothing

End Sub

Private Function QualifyMacroName(ByVal book As Workbook, ByVal procedure As String) As String

QualifyMacroName = "'" & book.FullName & "'!" & procedure

End Function

Public Function Create(ByVal procedure As String, Optional instance As Object = Nothing, Optional ByVal initialLabelValue As String, Optional ByVal initialCaptionValue As String, Optional ByVal completedSleepMilliseconds As Long = 1000, Optional canCancel As Boolean = False) As ProgressIndicator

Dim result As ProgressIndicator

Set result = New ProgressIndicator

result.Cancellable = canCancel

result.SleepMilliseconds = completedSleepMilliseconds

If Not instance Is Nothing Then

Set result.OwnerInstance = instance

ElseIf InStr(procedure, "'!") = 0 Then

procedure = QualifyMacroName(Application.ActiveWorkbook, procedure)

End If

result.ProcedureName = procedure

If initialLabelValue vbNullString Then result.ProgressView.ProgressLabel = initialLabelValue

If initialCaptionValue vbNullString Then result.ProgressView.Caption = initialCaptionValue

Set Create = result

End Function

Friend Property Get ProgressView() As ProgressView

Set ProgressView = view

End Property

Friend Property Get ProcedureName() As String

ProcedureName = this.procedure

End Property

Friend Property Let ProcedureName(ByVal value As String)

this.procedure = value

End Property

Friend Property Get OwnerInstance() As Object

Set OwnerInstance = this.instance

End Property

Friend Property Set OwnerInstance(ByVal value As Object)

Set this.instance = value

End Property

Friend Property Get SleepMilliseconds() As Long

SleepMilliseconds = this.sleepDelay

End Property

Friend Property Let SleepMilliseconds(ByVal value As Long)

this.sleepDelay = value

End Property

Public Property Get CurrentProgress() As Double

CurrentProgress = this.currentProgressValue

End Property

Public Property Get Cancellable() As Boolean

Cancellable = this.canCancel

End Property

Friend Property Let Cancellable(ByVal value As Boolean)

this.canCancel = value

End Property

Public Property Get IsCancelRequested() As Boolean

IsCancelRequested = this.cancelling

End Property

Public Sub AbortCancellation()

Debug.Assert this.cancelling

this.cancelling = False

End Sub

Public Sub Execute()

view.Show vbModal

End Sub

Public Sub Update(ByVal percentValue As Double, Optional ByVal labelValue As String, Optional ByVal captionValue As String)

On Error GoTo CleanFail

ThrowIfNotInitialized

ValidatePercentValue percentValue

this.currentProgressValue = percentValue

view.Update this.currentProgressValue, labelValue

CleanExit:

If percentValue = 1 Then Sleep 1000 ' pause on completion

Exit Sub

CleanFail:

MsgBox Err.Number & vbTab & Err.Description, vbCritical, "Error"

Resume CleanExit

End Sub

Public Sub UpdatePercent(ByVal percentValue As Double, Optional ByVal captionValue As String)

ValidatePercentValue percentValue

Update percentValue, Format$(percentValue, "0.0% Completed")

End Sub

Private Sub ValidatePercentValue(ByRef percentValue As Double)

If percentValue > 1 Then percentValue = percentValue / 100

End Sub

Private Sub ThrowIfNotInitialized()

If this.procedure = vbNullString Then

Err.Raise ProgressIndicatorError.Error_NotInitialized, TypeName(Me), ERR_NOT_INITIALIZED

End If

End Sub

Private Sub view_Activated()

On Error GoTo CleanFail

ThrowIfNotInitialized

If Not this.instance Is Nothing Then

ExecuteInstanceMethod

Else

ExecuteMacro

End If

CleanExit:

view.Hide

Exit Sub

CleanFail:

MsgBox Err.Number & vbTab & Err.Description, vbCritical, "Error"

Resume CleanExit

End Sub

Private Sub ExecuteMacro()

On Error GoTo CleanFail

Application.Run this.procedure, Me

CleanExit:

Exit Sub

CleanFail:

If Err.Number = VBERR_MEMBER_NOT_FOUND Then

Err.Raise ProgressIndicatorError.Error_ProcedureNotFound, TypeName(Me), ERR_PROC_NOT_FOUND

Else

Err.Raise Err.Number, Err.Source, Err.Description, Err.HelpFile, Err.HelpContext

End If

Resume CleanExit

End Sub

Private Sub ExecuteInstanceMethod()

On Error GoTo CleanFail

Dim parameter As ProgressIndicator

Set parameter = Me 'Me cannot be passed to CallByName directly

CallByName this.instance, this.procedure, VbMethod, parameter

CleanExit:

Exit Sub

CleanFail:

If Err.Number = VBERR_MEMBER_NOT_FOUND Then

Err.Raise ProgressIndicatorError.Error_ProcedureNotFound, TypeName(Me), ERR_PROC_NOT_FOUND

Else

Err.Raise Err.Number, Err.Source, Err.Description, Err.HelpFile, Err.HelpContext

End If

Resume CleanExit

End Sub

Private Sub view_Cancelled()

If Not this.canCancel Then Exit Sub

this.cancelling = True

End Sub

The Create method is intended to be invoked from the default instance, which means if you’re copy-pasting this code into the VBE, it won’t work. Instead, paste this header into notepad first:

VERSION 1.0 CLASS

BEGIN

MultiUse = -1 'True

END

Attribute VB_Name = "ProgressIndicator"

Attribute VB_GlobalNameSpace = False

Attribute VB_Creatable = False

Attribute VB_PredeclaredId = True

Attribute VB_Exposed = True

Then paste the actual code underneath, save as ProgressIndicator.cls, and import the class module into the VBE. Note the VB_Exposed attribute: this makes the class usable in other VBA projects, so you could have this progress indicator solution in, say, an Excel add-in, and have “client” VBA projects that reference it. Friend members won’t be accessible from external code.

Here I’m Newing up the ProgressView directly in the Class_Initialize handler: this makes it tightly coupled with the ProgressIndicator. A better solution might have been to inject some IProgressView interface through the Create method, but then this would have required gymnastics to correctly expose the Activated and Cancelled view events, because events can’t simply be exposed as interface members – I’ll cover that in a future article, but the benefit of that would be loose coupling and enhanced testability: one could inject some MockProgressView implementation (just some class / not a form!), and just like that, the worker code could be unit tested without bringing up any form – but then again, that’s a bit beyond the scope of this article, and I’m drifting.

So the Create method takes the name of a procedure, and uses it to set the ProcedureName property: this procedure name can be any Public Sub that takes a ProgressIndicator parameter. If it’s in a standard module, nothing else is needed. If it’s in a class module, the instance parameter needs to be specified so that we can later invoke the worker code off an instance of that class. The other parameters optionally configure the initial caption and label on the form (that’s not exactly how I’d write it today, but give me a break, that code is from 2015). If the worker code supports cancellation, the canCancelparameter should be supplied.

The next interesting member is the Execute method, which displays the modal form. Doing that soon triggers the Activated event, which we handle by first validating that we have a procedure to invoke, and then we either ExecuteInstanceMethod (given an instance), or ExecuteMacro – then we Hide the view and we’re done.

ExecuteMacro uses Application.Run to invoke the procedure; ExecuteInstanceMethod uses CallByName to invoke the member on the instance. In both cases, Me is passed to the invoked procedure as a parameter, and this is where the fun part begins.

The worker code is responsible for doing the work, and uses its ProgressIndicator parameter to Update the progress indicator as it goes, and periodically check if the user wants to cancel; the AbortCancellation method can be used to, well, cancel the cancellation, if that’s needed.

Client & Worker Code

The client code is responsible for registering the worker procedure, and executing it through the ProgressIndicator instance, for example like this:

Public Sub DoSomething()

With ProgressIndicator.Create("DoWork", canCancel:=True)

.Execute

End With

End Sub

The above code registers the DoWork worker procedure, and executes it. DoWork could be any Public Sub in a standard module (.bas), taking a ProgressIndicator parameter:

Public Sub DoWork(ByVal progress As ProgressIndicator)

Dim i As Long

For i = 1 To 10000

If ShouldCancel(progress) Then

'here more complex worker code could rollback & cleanup

Exit Sub

End If

ActiveSheet.Cells(1, 1) = i

progress.Update i / 10000

Next

End Sub

Private Function ShouldCancel(ByVal progress As ProgressIndicator) As Boolean

If progress.IsCancelRequested Then

If MsgBox("Cancel this operation?", vbYesNo) = vbYes Then

ShouldCancel = True

Else

progress.AbortCancellation

End If

End If

End Function

The Create method can also register a method defined in a class module, given an instance of that class – again as long as it’s a Public Sub taking a ProgressIndicator parameter:

Public Sub DoSomething()

Dim foo As SomeClass

Set foo = New SomeClass

With ProgressIndicator.Create("DoWork", foo)

.Execute

End With

End Sub

Considerations

In order to use this ProgressIndicator solution as an Excel add-in, I would recommend renaming the VBA project (say, ReusableProgress), otherwise referencing a project named “VBAProject” from a project named “VBAProject” will surely get confusing 🙂

Note that this solution could easily be adapted to work in any VBA host application, by removing the “standard module” support and only invoking the worker code in a class module, with CallByName.

Conclusion

By using a reusable progress indicator like this, you never need to reimplement it ever again: you do it once, and then you can use it in 200 places across 100 projects if you like: not a single line of code in the ProgressIndicator or ProgressView classes needs to change – all you need to write is your worker code, and all the worker code needs to worry about is, well, its job.

Don’t hesitate to comment and suggest further improvements, suggestions are welcome – questions, too.

Downloads

I’ve bundled the code in this article into a Microsoft Excel add-in that I uploaded to dropbox (Progress.xlam).

Enjoy!