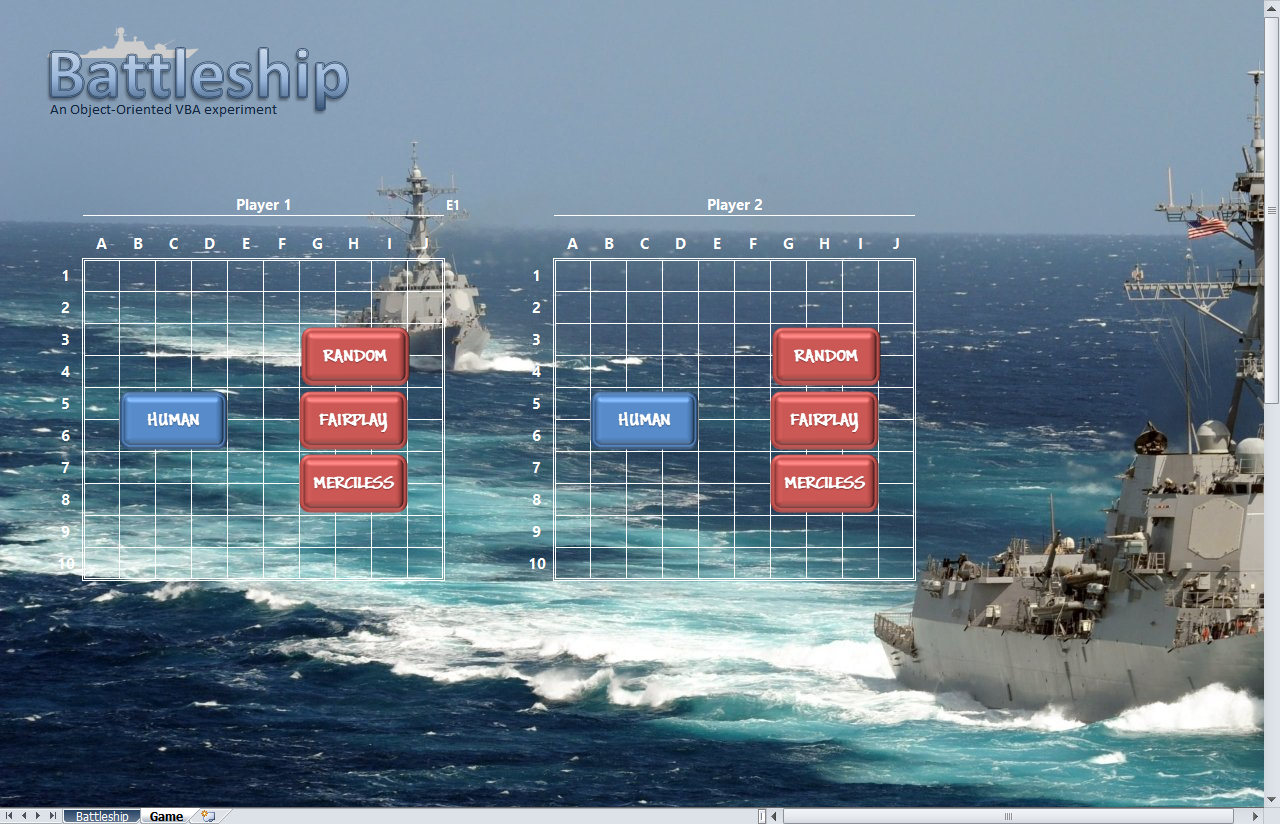

Whether VBA can do serious OOP isn’t a question – it absolutely can: none of the SOLID principles have implications that disqualify VBA as a language, and this means we can implement dependency injection and inversion of control. This article will go over the general principles, and then subsequent articles will dive into various dependency injection techniques you can use in VBA code.

A quick summary of these fundamental guidelines, before we peek at DI and IoC:

SOLID

Single Responsibility Principle

Split things up, and then some. Write loop bodies in another procedure, extract if/else blocks into other small specialized procedures. Do as little as possible, aim for each procedure to have a well-defined single responsibility.

Open/Closed Principle

Designing classes that are “open for extension, but closed for modification” is much easier said than done, but definitely worth striving for; by adhering to the other SOLID principles, this one just naturally falls into place. In a nutshell, you’ll want to be able to add features by extending a class rather than modifying it (and risk breaking something) – the only code you need to think about is the code for the new feature… and how you’re going to be testing it.

Liskov Substitution Principle

Say you write a procedure that takes an IFooRepository parameter. Whether you invoke it with some SqlFooRepository, MySqlFooRepository, or FakeFooRepository, should make no difference whatsoever: each implementation fulfills the interface’s contract, each implementation could be swapped for another without altering the logic of the procedure.

Interface Segregation Principle

Write small, specialized interface with a clear purpose, that won’t likely need to grow new members in the future: IFooRepository.GetById is probably fine, but IFooRepository.GetByName looks like someone had a specific or particular implementation in mind when they designed the interface, and now you need to implement a GetByName method for a repository where that makes no sense.

Dependency Inversion Principle

Depend on abstractions, not concrete implementations – your code has dependencies, and you want them abstracted away behind interfaces that you receive as parameters.

What is a dependency?

You’re writing a procedure, and you need to invoke a method that belongs to another object or module – say, MsgBox: with it your procedure can warn the user of an error, or easily get a yes/no answer. But this ability comes with a cost: now there’s no way to invoke that procedure without popping a message box and stopping execution until it’s dismissed. Hard-wired dependencies make unit testing difficult (if not impossible), so we inject them instead, as abstractions.

And dependency injection?

MsgBox is a bad example – Rubberduck’s FakesProvider already lets you configure MsgBox calls any way your testing requires, and no pop-up ..pops up. But let’s say the procedure needs to do things to a Worksheet.

We could make the procedure take a Worksheet parameter, and that would be method injection.

Since we’re in a class module (right?), we could have a Property Set member that takes a Worksheet value argument and assigns it to a Worksheet instance field that our method can work with, and that would be property injection.

We could have a factory method on our class’ default instance, that receives a Worksheet argument and property-injects it to a New instance of the class, then returns an instance of the class that’s ready to use (behind an interface that doesn’t expose any Property Set accessor for the injected dependencies), and that would be as close to the ideal constructor injection as you could get in a language without constructors.

What “control” is inverted, and why?

When a method News up all its dependencies, it’s a control freak that doesn’t let the outside world know anything about what objects it needs to do its job: it’s a black box that other code needs to take as “it just works”, and we can’t do much to alter how it works.

With inversion of control (IoC), you give up that control and let something else New things up for you, and that’s why Dependency Injection (DI) goes hand-in-hand with it. IoC implies completely reversing the dependency graph. Take a UserForm that reads from / writes to a worksheet, with code-behind that implements every little bit of what needs to happen in CommandButton1_Click handlers – a “Smart UI” – reversing the dependency graph means the form’s code-behind is now only concerned about the data it needs to present to the user, and the data it needs to collect from the user; the CommandButton1 button was renamed to AcceptButton, and its Click handler does one single thing: it invokes a SaveChangesCommand object’s Execute method, and everything that was in that click handler is now in that ICommand implementation. The command knows nothing of any userform; it works with the model, that it receives in an Object parameter to its Execute method.

It all comes down to one thing: testability. You want to test your commands and what they do, how they manipulate the model – so you pull as much as possible out of UI-dependent code and into specialized classes that only know as much as they need to know. The form’s code-behind (aka the view) knows about the model, the commands; the model knows about nothing but itself; the commands know about the model; a presenter would know about both the view and the model, but shouldn’t need to care for commands.

If none of the components create their dependencies / if all components have their dependencies injected, then if we follow the dependency chain we arrive to an entry point: in VB6 that would be some Public Sub Main(); in VBA, that could be any Public Sub procedure / “macro” in a standard module, or any Worksheet or Workbook event handler. These entry points all need to New up (or otherwise provide) everything in the dependency graph (e.g. class1 depends on class2 which depends on class3 and class4, …), and then invoke the desired functionality.

What is testable code?

Testable code is code for which you can fully control/inject all the dependencies of that code. This is where coding against abstractions pays off: you can leverage polymorphism and implement test doubles / stubs / fakes as needed. The presence of a New keyword in a method is a rather obvious indicator of a dependency; it’s the implicit dependencies that are harder to spot. These could be a MsgBox prompt, a UserForm dialog, but also Open, Close, Write, Kill, Name keywords, or maybe ActiveSheet, or ActiveWorkbook implicit member calls against a hidden global object; even the current Date can be a hidden dependency if it’s involved in behavior you want to cover with one or more unit tests. The Rnd function is definitely a dependency as well.

SOLID code is inherently testable code. If you write the tests first (Test-Driven Development / TDD), you could even conceivably end up with SOLID-compliant code out of necessity.

Say you want to bring up a dialog that collects some inputs, and one of these inputs needs to be a decimal value greater than or equal to 0 but less than 1 – what are the odds that such validation logic ends up buried in some TextBox12_Change handler (and duplicated in 3 places) in the UserForm module if the problem is tackled from a testability standpoint? That’s right: exactly none.

If the first thing you do is create a MyViewModelTests module with a MySpecialDecimal_InvalidIfGreaterThanOne test method, there’s a good chance your next move could be to add a MyViewModel class with a MySpecialDecimal property – be it only so that the test method can compile:

'@TestMethod("ValidationTests")

Public Sub MySpecialDecimal_InvalidIfGreaterThanOne()

Dim sut As MyViewModel

Set sut = New MyViewModel

sut.MySpecialDecimal = 42

Assert.IsFalse sut.IsValid

End Sub

So we need this MyViewModel.IsValid member now:

Public Property Get IsValid() As Boolean

End Property

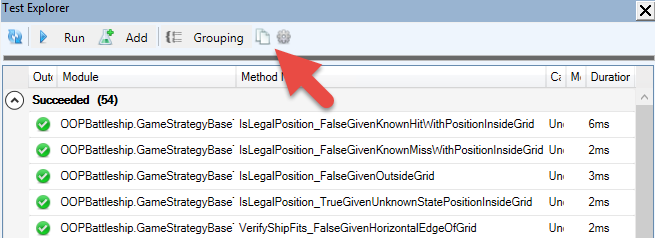

At this point we can run the test in Rubberduck’s Test Explorer, and see it fail. Never trust a test you’ve never seen fail! The next step is to write just enough code to make the test pass:

Public Property Get IsValid() As Boolean

IsValid = MySpecialDecimal < 1

End Property

This prompts us to write another test that we know would fail:

'@TestMethod("ValidationTests")

Public Sub MySpecialDecimal_InvalidIfNegative()

Dim sut As MyViewModel

Set sut = New MyViewModel

sut.MySpecialDecimal = -1

Assert.IsFalse sut.IsValid

End Sub

So we tweak the code to make it pass:

Public Property Get IsValid() As Boolean

IsValid = MySpecialDecimal >= 0 And MySpecialDecimal < 1

End Property

We then run the whole test suite, to validate that this change didn’t break any green test, which would mean a regression bug was introduced – and the red test is telling you exactly which input scenario broke.

In a vanilla VBE, OOP quickly gets out of hand, for any decently-sized project: wading through many class modules in the legacy editor, locating implementations of the interfaces you’re coding against – things that you would seamlessly deal with in a modern IDE, become excruciatingly painful when modules are all listed alphabetically under one single “classes” folder, and when Ctrl+F “Implements {name}” is the only thing that can help you locate interface implementations.

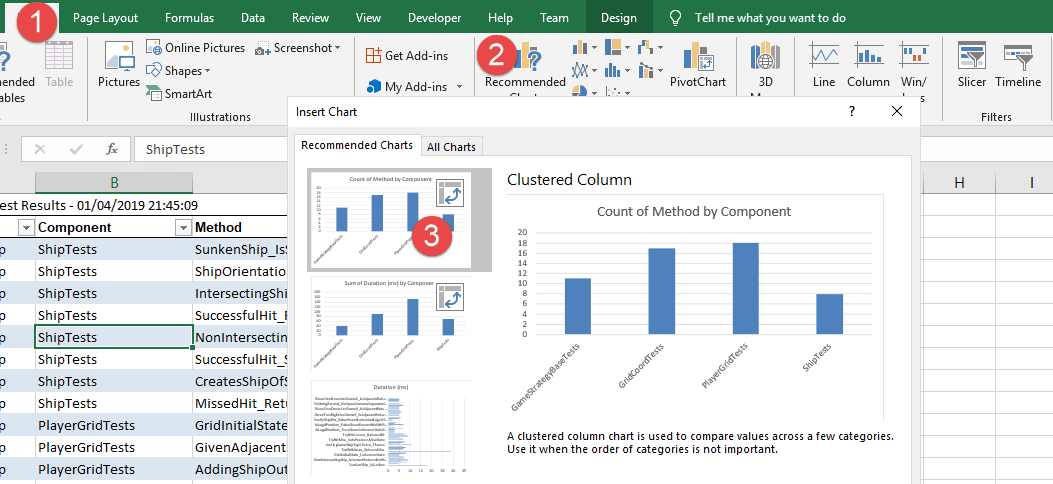

Rubberduck not only addresses the organization of your OOP project (with “@Folder” annotations that let you organize & regroup modules by functionality) and enhances navigation tooling (“find all implementations”, “find all references”, “find symbol”, etc.), it also provides a unit testing framework, so that testing your VBA code is done the same way it’s done in other languages and modern IDEs, with Assert expressions that make or break a green test.

But if you write unit tests for your object-oriented VBA code, you’ll quickly notice that when your tests need to inject a fake implementation of a dependency, a consequence is that you often end up with a lot of “test fake” classes whose sole purpose is to support unit testing. This is double-edged, because you need to be careful that you’re testing the right thing (i.e. the actual object/method under test) and not whether your test fake/stub is behaving correctly.

Rubberduck has well over 5K unit tests, and most of them would be very hard to implement without the ability to setup proper mocking. Using the popular Moq framework, we are able to create and configure these “test fakes” without actually writing a class that implements the interface we need to inject into the component we’re testing.

Soon, these capabilities will land in the VBA landscape, with Rubberduck’s unit testing tools wrapping up Moq to let VBA code do exactly that.